Interview

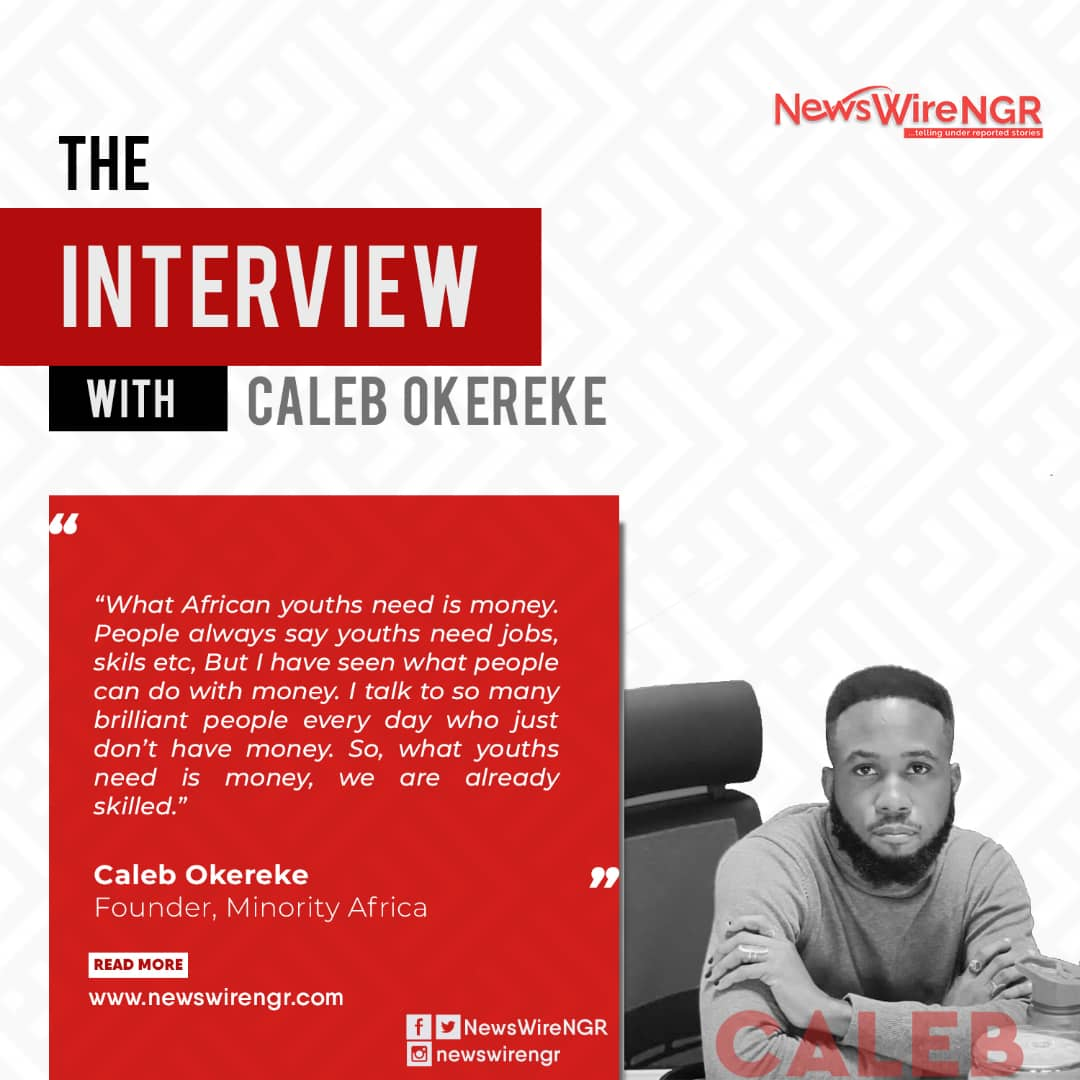

INTERVIEW: Caleb Okereke, 22-year-old Minority Africa Founder changing Africa’s narrative

Conversations about Africa in the Western world is centred on manoeuvring poverty and violence that it is sometimes difficult to know what else is happening.

Less attention is given to the positive trends and underlying successes of the continent.

Fortunately, the continent has grown its own storytellers and more young Africans – the new generation – are striving to change the negative narrative.

It is 2021 however, and the continent is guilty of what it accused the Western world of committing. While the continent on one hand laments the world of stifling its voice, various minority groups in the content are also gasping for breath, hoping to tell their stories.

This voice deficit was what then 20-year-old Caleb Okereke discovered in 2019 when he decided to start Minority Africa.

Having worked as an independent journalist for some of the world’s biggest news organizations (Aljazeera to BBC, and DW) in-between Nigeria and Uganda; he discovered in a conversation with Jeffrey Daniel that “There’s so much we don’t know as Africans, so much history has been erased.”

Almost three years since starting Minority Africa, Okereke, from Uganda gets over the phone with NewsWireNGR’s Oladele Owodina to discuss why it is important to give minority groups a voice and how he hacked a way to run a profitable news platform while he is a university student.

“When people ask me, what I say is that Minority Africa is a digital publication providing multimedia solutions on African minority communities and persons using an approach that is data-driven and highly interactive but it is a lot more than that.” Caleb Okereke.

You’re a Nigerian in East Africa’s Uganda, how did you find yourself there?

I came to Uganda first to study at Cavendish University (I’ll be graduating next month, August). And then while studying, I started Minority Africa in my second year. So yeah, that’s really it. That’s how I ended up here.

When did you go to study?

I came in 2018, and I was living in Lagos before then.

How has life been as a Nigerian in Uganda? You have a business there and your name easily exposes you as a Nigerian

It’s been okay. I always say Uganda is one of my most favorite countries in the world because of the people. I have had a good network of people who have really supported me. So, we for instance are registered in Mauritius, we have a branch office in Uganda and all these are possible because of the network of people I have around. So yep, it’s been okay.

Will you be back in Nigeria?

Probably not. I don’t plan on it. I will always visit Nigeria, but I don’t want to live in Nigeria.

Uganda must be so chilled

No, I am not going to live in Uganda either for so long and I will not live in Nigeria either.

Going to Uganda seems very different … why the choice?

It was really a bit of frustration. I was frustrated and needed a place to go right away. I initially was supposed to study medicine, that is like every Nigerian parent’s plan, but I rebelled and was like I am not doing medicine. Because I never did art, I did sciences the whole time.

So, I came to Uganda. And they had a program in journalism and all I needed was my O’Level results, so I was nice, I could get a hold of this program.

I applied and was given admission to study journalism; I told my parents, and they said I’m not going anywhere, I said you people can’t control my life, even though I still begged for a while and eventually they let me go a semester later, but I had to defer my admission for a semester. And yeah, that was it.

They must have made peace with the decision now

Oh, they got over it. I think that was the first time I learnt that people will always get over things. They are okay; they are very pleased now.

Lucky you with the exposure to diverse cultures. What have been your most memorable moments?

I have had many memorable moments in my life. One memorable moment for me was with my grandfather. And I say that because he inspired me, not necessarily to write but to keep at it, because he was a journalist as well. He would tell me stories about his 30 years journey as a journalist. Actually, he was still working as a journalist even before he died. So yeah, I think lots of memorable moments involved talking about writing and journalism.

How did you get started with Minority Africa?

In my first semester in school, I participated in an intra-university media competition. The idea was for us to go head-to-head with each other in a competition for journalism. It was a 3-day event. We had to produce news stories within 3 days, produce a whole news bulletin, do social media, basically to be a media company, but for student journalists.

When we finished the competition, I somehow won an award for the story I did, which was very interesting to me because I didn’t know so much about journalism. After that competition, the winners had a chance to apply for a fellowship program.

So I applied for the fellowship program, which was six months of training. It was an aggressive month of media training and I stayed on it. During the six months, there was so much emphasis on us innovating and starting media companies. And it was then I started thinking of Minority Africa and also freelanced for mainstream media publications. So, it suddenly became more personal for me because I realised that the stories I wanted to see told were not being told. I also realised how much defending we had to do if we wanted a story to be told, like in that sense.

So, it struck me that there needs to be a platform that has to tell minority stories and I then realised that such a platform doesn’t exist yet. I then had to be the one to start it, so yeah, that was how Minority Africa was born. I sat down; I thought of the areas that had problematic coverage and sometimes no coverage at all in African media. When I identified these areas, I was able to start it.

Do you think it’s wrong to say Africa has a problem with poor reportage?

There is a part people say Africa is poorly represented, and that’s definitely a problem but my own concern was with minority coverage. The reason I started Minority Africa was not because of the problematic coverage of Africa as a whole but for the problematic coverage of minorities, whether in Africa media and elsewhere.

I do think that the coverage of Africa is improving but there is also the coverage of Africa minorities which is even more problematic, like the way newspapers sometimes report gay people, homosexuals or the way we see a lot of inspirational content of physically challenged persons and they are still going on. There’s change, if at all, but it is gradual, and we at Minority Africa see ourselves as a platform that serves to foster and anchor that change as it happens.

Alongside Minority Africa, are there other platforms you know are doing what you do?

Yes, actually there are. I know of several platforms that are much more focused than we are, and by focused, I mean more niche. For instance, Kiki Mordi had Document Women, which is incredible and which I really like. I have talked about it in my newsroom, office and among my colleagues as an example of what proper coverage of women should be like. There’s one in Uganda, which is doing sectional minority stories, there’s a publication in Nigeria which is also doing sexual minority stories as well. These are the ones I can remember for now.

Walk me through the story that got you an award when you were in school.

It was a story about social media and fake news. Part of the requirements for the award was that you had to get the story from the venue of the event. The event was for 3 days and on the first day, there were panel discussions. On the second day, you’ll produce a story and news bulletin that you had come up with from the panel discussion and then on the 3rd day, you would present the news bulletin. So there was a panel discussion around fake news and social media, which was how I got the story idea and did the story.

What are the challenges of schooling and running a media platform?

It’s been a ride of a lifetime. At first, I thought it would be impossible but what I think really helped me was the fact that last year my school moved online due to the pandemic and I could study and work from home. All my school learnings and exams were all done online and that sort of made it much easier. Because before then, when we started Minority Africa in November, there had been months and months of preparation before launch, and combining physical classes during those periods was just crazy. And even now, it’s still not easy, but it is doable. And I must say, my school is really supported and my lecturers are aware and are supportive.

What are your favorite stories published on the platform?

For Pride Month last month, we did this story where we wanted to track Pride matches across Africa. We tracked one in South Africa, so we have a piece on it where we interviewed people who attended the match and have pictures to share. It would be the only story about it on the internet. You’ll only find Wikipedia or journal entries elsewhere, but we will be the first article that will put together all of these pieces into one in Africa.

I think all the pieces that have been published on Minority Africa are my favorites. And I also like the one that talked about how black hair is extensively being policed in schools in Africa, whereas white people can go with their hair as they are. This doesn’t make sense because I am in black country, so why am I being policed in my own home? So we did a piece on it and many people connected to it and it went quite viral. I think those two stand out for me.

What kind of stories can people who want to send their pitches send?

We are looking to do more video content, so we put out a call for multimedia reporters in North and Southern Africa because we don’t feel like we have covered those areas enough and we want to. So we put out that call and we want to do more disability stories. We have done some, but we want to do more. From our pitches, we only publish solution stories, and in a few cases opinion pieces like Pride Month. This is because we try to avoid highlighting problems without giving solutions.

On Twitter, I tend to see more claims that we need solution journalism in Africa. What is the thing about this solution journalism?

A good question. There’s a platform called The Solution Journalism Network which has been since 2012 or earlier, I’m not sure. I am an alumnus of their fellowship that encourages solution journalism; I am one of their fellows. What was very special about the fellowship to me and about the concept of solution journalism, especially with minority stories is that people have had their narratives misinterpreted or misinformed. Like when you read a piece about a gay person, for example in Nigerian news media, it is either someone has been lynched somewhere or someone had a sex tape released and people are mocking them or someone is being misgendered or a story about disability, it is either to inspire, like if this person could do this having no legs, what more you. So when you look at situations like this, it becomes even much more imperative to practice solution journalism.

Do these solution-oriented stories generate different responses to problem-oriented stories?

Well, here in Minority Africa, we do solution-oriented stories rather than problem-oriented stories, so I can’t say which gets more response. But I know that SJN, which is Solution Journalism Network, has a research that shows that solution journalism keeps readers more hopeful, makes them want to read news more, and trust a platform more.

What worries you the most about solution journalism adoption across Africa?

I think what worries me the most is the confusion that solution journalism is only positive news, because it is not. And that takes away from what the core is about, because if you only write about good news, what is the point of news? It is positive news, it’s not a feel-good story, it’s not an inspirational story. It really isn’t. and I hope that can become clearer.

You earlier mentioned that your grandma was a nurse during the Biafra war. What other Biafra story still lingers with you?

You know when you’ve heard so much about something, it’s hard for you to pick one. I’m sorry I can’t figure out one at the moment because I don’t have a single recollection of the memories. Like I don’t know of a single instance where my grandmother treated a particular person on the balcony, but I know she treated people on the balcony during the war. I know that my grandfather worked with Ojukwu very closely and traveled across the state together because he was his very right-hand journalist. They worked together and started Radio Biafra, so he was all of that.

What is the name of your grandfather?

He’s called Mazi Philips Okereke

I’m trying to piece this, was he mentioned in Chinua Achebe’s piece on the Civil war, There Was A Country?

I don’t know because I actually haven’t read There Was A Country. All I know is that my grandfather worked with Chinua Achebe, he also worked with NTA and then Radio Nigeria at some point and he became the General Manager of NTA before retiring. I haven’t read There Was A Country, but it is possible. And I don’t think there’s so much material on my grandfather. But before he died, I actually did a series of recordings with him. So, I’m going to create a sort of online repository of his life.

It seems journalism or writing runs in the family. Is your dad a communication person too?

Yeah, my dad did a bit of journalism for a while but now he sort of does Public Relations, I think. And that is a sort of why they didn’t want me to study journalism because they were like there was no money in journalism, because they knew it so well, I think.

The big talk of money and journalism. You obviously don’t want to be one ..

No, I don’t, and it’s not like I don’t want to be broke, it is just that I can’t afford to be broke. It is really impossible for me because I just can’t afford to be. I’m not saying this because I came from wealth, because I absolutely did not, and I’m not saying this because I have money, because I don’t. but I also know I can’t afford to be poor; it is impossible. So, I do my journalism with this in mind. I think that work is important and I feel that the arts should be equally funded and paid as the sciences because we are both relevant and needed.

So, for me, I have a mental state that I vehemently know that I refuse to be poor. I think what has really helped me is that I started writing very early, like at 16 years old, all of this was unpaid work. I started my career doing unpaid work like everybody else for blogs and newspapers, and magazines. Just for my name to be somewhere. I think that is necessary for everybody and I have done that and I did that early.

So now I’m going to be 23 next month, and sort of know that I can’t do unpaid work anymore, it is impossible. And the question is even like what kind of paid work I do. I always tell my company that they don’t pay me how much I really deserve, they really don’t, they can’t afford me yet. And I get it, it is also still my company right, I started it because I wanted to do something. And it won’t always be that way. One day I will be able to afford the salary I want to pay myself.

I know it is a mindset thing and if there’s no money, I will actually live and earn, that is the truth. I will not do Minority Africa if I don’t have the money to do it, I will leave it and go away. I might still do it but I won’t do it with the same level of intensity that it needs to be done. And not because I want money to buy a house in Dubai and even the fact that I’m on this phone call has a financial cost, that I can talk and have glasses on, I can’t see without my glasses is a financial cost. That I have a laptop to seclude a meeting is all a financial cost. And that cost has to be paid for by something. So if Minority Africa is not paying it, I will go elsewhere or probably go be a doctor, eventually. So, for me, I don’t put passion before money; they are parallel; it is not one over the other. I have passion and I also want money.

You have done a lot at 23

I am not even 23 years yet, it’s until next month. So yeah, I’m actually quite young.

Do people express shock when they know your age?

I don’t often tell people (my age), I only started saying it recently because when I started Minority Africa at 21. I didn’t use to say it because when I was writing things on BellaNaija, I was like 16 years old. I just thought people won’t take me seriously even though I knew I had great ideas to share if they knew how old I was. It was influenced by what I had seen; I remember people who ghosted me when I told them how old I was, so I was sort of like this is not working, so I stopped saying my age unnecessarily. It makes me feel good but I don’t think I have done anything spectacular for my age, people have done more things at my age, and I don’t think I have done less, I am just doing, I’m just into doing and that is okay.

What do you think is the biggest challenge for youths across Africa?

I think what youths need is money. People always say youths do things, killings because there are no jobs, this and that. And I say this as a person who has seen what people can do with money. I talk to so many brilliant people every day who just don’t have money. So, what we need is money, we just don’t need skills. Of course, there are the killings that happen, but it is like going to driving school when you don’t have a car. You can give me a skill but if I don’t have money, I won’t be able to implement them. If I had a million dollars today, I will do the best for Minority Africa, but I don’t. and I even have some money, but some people don’t have anything at all. So, I think what we need is money. And I’m not sure how that connects to solution journalism but we definitely need money.

What fellowship did you get when you won the competition?

It was just a 6 months training for journalists, because like then, I didn’t know what MA was. We got our first money from Solutions Journalism Network, which was 2,500 USD. This year we got 34,000 USD. Next year, the grace of God will guide us.