Interview

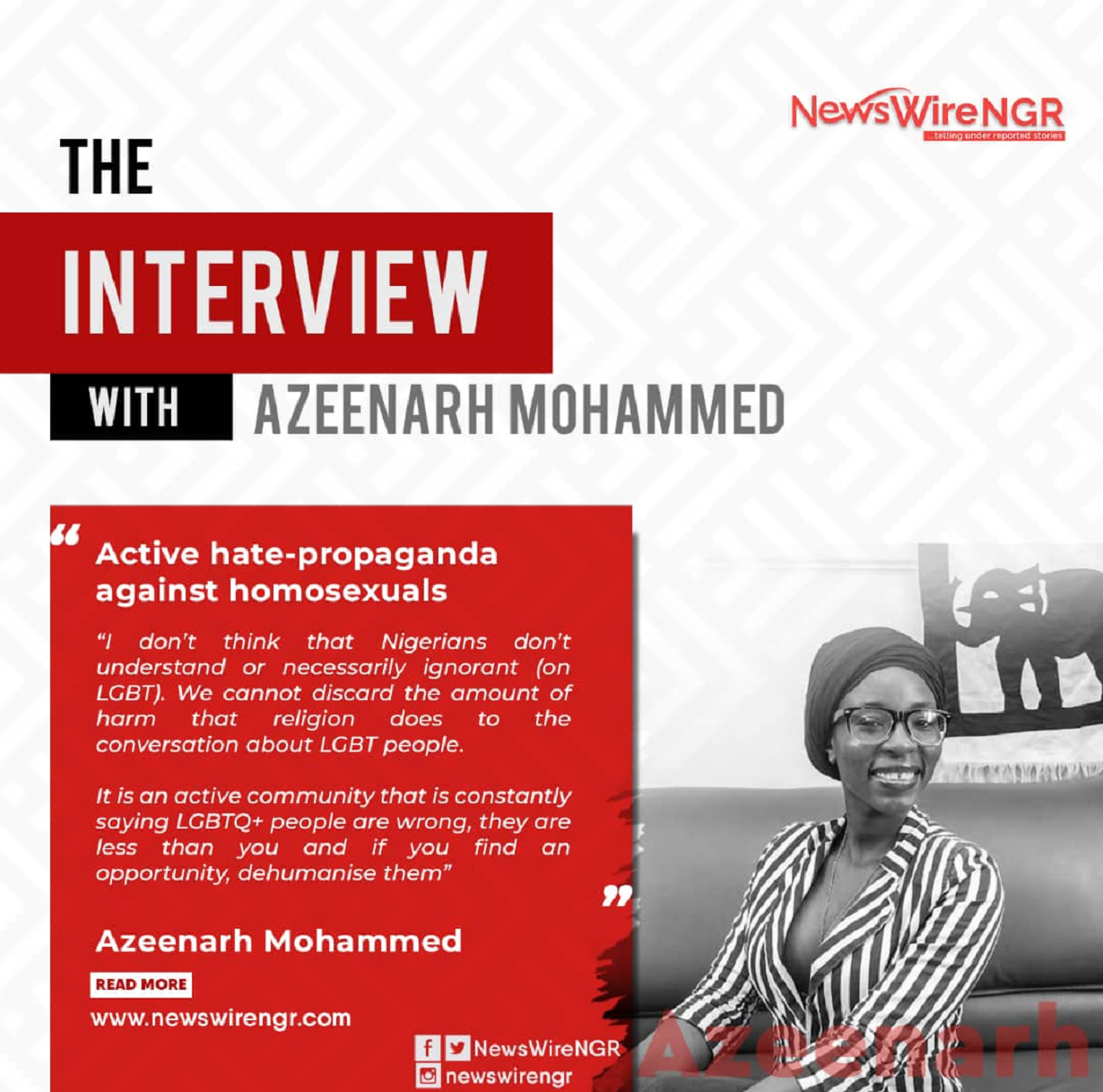

[INTERVIEW] Queer and Muslim: Azeenarh Mohammed blurring the parallel lines of LGBTQ+ and religion

Azeenarh Mohammed is an accomplished woman. She is an upper-class Fulani lady that has made a name for herself in the legal profession, as a human rights activist, as an author and in the tech space.

Despite these; her biggest win she says is coming to terms with her sexuality.

“I used to be a full covering hijabite,” Azeenarh says, reminiscing her time growing up in a conservative northern Nigeria.

“Despite the fact that I knew early I was queer, I thought I had to live my life and be a good Muslim girl, marry, have kids and all of that”.

Having won her impostor battle and coming out as a lesbian, Azeenarh used the voice afforded by her class privilege to speak for the Nigerian queer community. She also provided legal services for those who got into trouble with the Nigerian government.

Today, Azeenarh is still an activist but she has left the legal practice and while making her paycheck in tech.

In this interview, she tells NewsWireNGR’s Oladele Owodina what it means to be queer in Nigeria, the declining rate of homophobia and the intersection between LGBT and religion.

“Being a lesbian should not preclude me for example from fasting. It should not preclude a gay man from leading prayer”Azeenarh Mohammed

LGBT activism dominates much of your description on the web, briefly tell us more about Azeenarh

I can’t believe that in 2021, I still get tagged with only the LGBT cap. I wear so many caps. Fundamentally, my formal training has been as a lawyer. I actually started out as a lawyer from like 2007 to 2011, all I did was practice law.

From the practice of law, I slowly moved into human rights and gender rights. That eventually grew a little too boring, especially in Nigeria where NGOs are not as political or radical as they can be but there’s a general lethargy for lack of a better word, it’s just about girls’ rights.

They only want to end suffering women and not actually dismantle the structures that are holding us back. So I think more and more out of women’s rights and humans’ rights, so I decided to go back and concentrate on tech.

So actually, what I do now, what pays my bills is actually working on tech. I currently work as the Africa Programme Manager for a tech programme. I’ve been working in digital and holistic security since 2013 and that’s what actually pays most of my bills. I’m always surprised when people ask me when they tell me that it’s always the LGBT that comes first. I’m just like I’m more than that. I’m a lot more than that.

What were your aspirations as a child?

As a child, I had very cliche aspirations. I either wanted to be a footballer or a pilot. My third choice was being a lawyer. So I guess I still ended up in the top three, but my first one was that I absolutely wanted to be a football player.

I was like if I get paid for enjoying football; I want that. So yeah, it goes with other things that I wanted to do while growing up.

I felt like if I was a pilot, I would just have a claim to my name and I could fly anywhere that I wanted to. You know the dreams of kids, but those were my top two.

Then I thought, if I eventually become a lawyer, look at that, I would be somebody who would stand up for my rights and the rights of others.

What does life mean to you?

The meaning of life to me is enjoying the diversity in which we have found ourselves. So for the longest time, I’ve been raised in a typical northern Muslim household.

This means that there’s very little individualism and more of a collective. You’re expected to do everything, not for yourself, but on behalf of your family. Everything you do, at the back of your mind, has to have an incline of how this would reflect on your wider extended family, on your culture and on your society.

So, that’s how we were raised. But I’ve grown to learn to remove the shackles and expectations of not just family, but society and I feel like more people have to.

I feel like life is too short, too unpredictable to live via the dreams of other people. I take it very personally. How do I see my life as a fulfilment of my own dreams and my own needs, not of others, not of society and I wish more people thought of it that way.

Our lives are a collective of moments, what specific moment led you to fight for LGBT rights?

Well to be honest, as you said, it was not a one-time thing. It was small little bits of things to get me to where I am today. I grew up in a house that even though it was a Muslim and it was conservative, it was also a very political family.

We were aware of our rights and the realities of what Nigeria is and how those involved heavily in politics. So I grew up around a ton of activists.

The discrimination basically based in northern Nigeria has always been a thing that has been in the back of my mind which was why I started working within human and women rights.

So within human and women rights, I slowly started varying more towards LGBT rights and this was deliberate. I felt like I needed to put my energy in where people were not putting their energy.

Too many people were working on a certain thing I was not interested in. I was thinking, where would I be of the most use? And my community at that point, the LGBTQ community was a community that nobody wanted to talk about. We really were taboo and nobody would even mention the fact that we existed.

Around 2006, 2007, conversations started in Nigeria as a whole about LGBT people. This had to do with the rising conversation and organising that gay men were organising around HIV, but it also had to do with the fact that globally, LGBT rights were moving forward.

I think that after Elton John married his partner, there was a whole conversation even within the National Assembly.

As that was happening, my mind was kept on going ding, ding, ding, but why are we stepping back in time if this isn’t a crime and we’re already forward, why then do we want to go backwards and criminalise something that has zero effect on the economy of the country, but will actually clamp down on the rights of people who are full Nigerians and have been guaranteed equality under the law.

So, as those conversations started, I knew that I wanted to speak up, but again as I had mentioned, I was raised in a conservative society where everything you do reflects on your family, on your culture, on the group that you belong to.

I always thought I would never be able to publicly speak about this issue, but again as I grew and became more independent, within my family, I was able to have conversations with them about the fact that I identify as a lesbian and the moment that they knew, it wasn’t a big deal, it was easy to start talking to other people about it.

I started to tell people who were not my family members. I had a general discussion with people.

I wrote an article about how my homosexuality did not change anything about me and I was more than the sum of just being somebody who belonged to the LGBTQ+ community.

It was small moments, but I knew at a point that I had the luxury of, for lack of a better word, class privilege, I could use that privilege to be able to put a voice to the collective struggle of LGBTQ+ in Nigeria, who at that point might not have been able to come out.

There seems to be a lack of depth when Nigerians talk about the LGBTQ community, what should Nigerians know about the LGBT community?

To be honest, I don’t think that they don’t understand and I don’t think that people are necessarily ignorant. We cannot discard the amount of harm that religion does to the conversation about LGBT people.

People go to churches and mosques and preachers and imams continue to reinforce the position of hatred against people who are LGBT.

So it’s not necessarily ignorance, but the active hate that is being put in people’s minds week in, week out. So, one side of it is religion.

The second side of it is culture and the fact that we generally, as a human race, don’t like things that are different from us.

We discriminate based on people that we perceive or feel are different from us and we want to dominate whatever it is that we can in various spaces. So yeah, Nigerians still have very problematic views about LGBT people, but it is actively thought.

They didn’t just wake up and due to lack of reading books or there’s a little bit of that because generally, Nigerians, we don’t read, we don’t find new information. But there is also an active community that is constantly saying LGBTQ+ people are wrong, they are less than you and if you find an opportunity, dehumanise them.

So, that’s part of the harm that is being done, but interestingly, during the discussion around passing the same-sex prohibition act, a couple of really interesting things happened.

READ ALSO: INTERVIEW: Oma Akatugba, the UNILAG dropout who became renowned international sports journalist

For example, in the past, nobody discussed LGBTQ+ issues completely. Right? It was kind of like a don’t ask, don’t tell taboo topic, but during that whole debate, people started being able to talk about it, right?

It became an opportunity where we normalised the idea that in fact, LGBT people exist. That they are fighting or that we’re having this conversation because they exist and we need to stop them.

So that actually put us on the map as a genuine community within Nigeria and within that also, many people started to come out or in defending the rights of LGBT. It put people on notice that actually, these folks have allies and I might actually be on the wrong side.

I know that in 2013, Pew research overtook worldwide research included in Nigeria and Nigeria polled as I think either the highest or the third-highest homophobic people in the world.

Ahead of places like even Saudi Arabia. There was a 98% intolerance level where they believe that LGBT people should not have access to education, should not have access to health care, should not have access to safe transportation, should not even have access to food and human dignity. That’s a lot of hate. 98% of the society believes that, as at 2013. But as at 2019 when the last poll was done, the numbers had gone significantly lower, even when SSMPA was passed in 2014, I think that 89% of Nigerians were in support of the law, right now, there’s only about 55% of Nigerians who have been polled, who are in support of the law, where almost 100% of people said that they will not accept friends or family members who were LGBT as at 2013.

Right now, over 30% of Nigerians say they will accept a friend or family member who identifies with LGBT.

So there are small shifts, they’re not big shifts, they are small and we are no longer a taboo; almost everybody you ask now will know at least one person who identifies as LGBT. So, small gains are being made that we have to be honest about.

Identifying as LGBT in Europe was once a taboo like in Nigeria, do you think we are in the right process of making Nigeria safe for members of the community?

Yeah, I believe that it’s going to be a long process, probably longer than it has taken in Europe and for various reasons, because Nigerians are just good at embracing differences instead of collective diversities and championing it as a good thing, right? We’re still having little squabbles about east, west and the south and the north. We’re still having squabbles about religion.

In fact, if there’s one thing that everybody agrees on, it’s collective homophobia. It’s one of the things most religions in Nigeria celebrate and accept. I do agree that we are on the right path.

History has shown that it takes little small steps to get equality and even after you get it in the courts, it takes time to change society.

Look at the Civil Rights Movement in America. Even though there are various laws that should protect people, people who are not white, people of colour and black people, in practice, it is still a work in progress.

I believe that, yes, we will get to a point where we will have legal equality with people who identify as not LGBT and eventually, society will catch up with the rest of it.

I mean, we’ll all get to a point where everybody will get to identify LGBT in their families and we’ll be okay with it because right now, a ton of people are in hiding and we’re forced to live a life of lies.

We will get to a place where more people are able to be more independent, to assert themselves, to choose their truth and live their truth.

It will be really hard for a pastor to go out there and be preaching about how we need to harm queer people when their son is gay, it’ll be much harder for politicians to be able to push laws if, for instance, their sister’s a lesbian and has a wife.

It will be much harder to just push all these inequality and various intolerances if the people that you’re trying to legislate against are people that are close to you.

It’s your best friend, it’s your teacher, it’s the person who owns the restaurant you enjoy going to. It’s your daughter’s best friend. All of those little things will lead to more acceptance generally.

The two popular religions in Nigeria are clearly homophobic, how can these religions exist side by side with homosexuality?

For me, it’s very clear. It’s not an issue. What you believe is yours, but you don’t enforce it on other people because the constitution guarantees us freedom of religion and freedom from religion.

The fact that you believe something does not mean that I have to practice what you believe. It’s literally like saying I’m on a diet, so nobody is allowed to eat or drink. That’s not how it works. I respect your right to religion, but you keep it where it belongs, in your life and not in other people’s lives and that is how it will work side by side.

I am a practising Muslim but it does not stop me from being a member of the LGBTQ+ community. There’s no difference between people who insist that we must do what they believe and Boko Haram because that is literally what Boko Haram is doing and saying.

They’re saying that because they believe in a certain way of practising Islam, everybody else must. So, if your pastor or imam is being exactly that way, he needs to have a good look in the mirror and see who his allies and people that he or she or they are modelling. It’s good to have religion, but you need to keep your religion to yourself and not enforce it on others.

I asked this because people say homosexuals want to force their way into religious spaces. Like a gay becoming the chief imam of a mosque …

Well, to be honest, everybody has a right to religion. You can’t take away people’s religion or the practice of religion. There are countless people who work within churches and mosques who are already LGBT. Just because they haven’t disclosed it does not denounce what their existence is and everybody has a right to it because I’m a lesbian should not preclude me for example from fasting. It should not preclude a gay man from leading prayer.

There are so many people who do various things and that should not take away from their religion. And this performance of Abrahamic religions when it comes to homosexuality is very weird because Abrahamic religions are at the epitome of picking and choosing religions.

They pick and choose the parts that they want to practice, but when it comes to homosexuality they draw a strong line. There are thousands of other things that the two books disagree with, that people practice on a daily basis. Like women speaking in church, like mixing different types of fabrics, like eating shellfish.

All of these things are things people do all of the time, but they found a way to defend them. You can be all of these things and when it comes to homosexuality, there’s a whole amount of pretence and ground standing and hypocrisy that Christianity, Islam, Judaism will always have in common.

I think that we need to remind ourselves to go back to the most important thing which is love and it is absolutely absurd to be able to continue to criminalise this love. Of all of the things, that one should be precluded from finding God and finding meaning. The person that you spend your life with should be the least of those.

What are the craziest stories you have heard within the Nigerian LGBT community?

Some of the craziest stories I have heard are some of the saddest. People who have complete acceptance from their family members and when people who are not their family find out, they end up being disowned.

There’s still this public act over the safety and security of members of our family. That’s like the wildest things I’ve heard. Where their parents were like “Oh it’s okay. I know who you are. I’ve always known since you were a child and you just need to keep it under wraps” and they one day, they get maybe caught in school for having boyfriends or girlfriends and then they come to the university and they get outed and then their parents disown them.

This is something they’ve always known, that they’ve made peace with, but because society now knows, they have to put on a performance and go on this show of how they do not tolerate something like this and I feel that is very unfortunate that we cut off family ties because of what some white people have brought to us inside books and we need to find our ways back to the bonds that actually tie us together.

There are tons of other really problematic stories I’ve heard of people being beaten and starved by family members in an attempt to convert them.

My question always is that you can’t convert someone’s sexuality. There are many people that say things like “Oh, a man tried to toast me” and I’m like “yeah, that’s okay.” They tried to toast you, it didn’t work out and they left.

They did not convert you, but what straight people actively try to do is change a queer person’s sexuality and that’s not how it works.

Like if you’re straight, you’re straight. You can’t change that. If you’re queer, you’re queer, you cannot change that. I think that we need to be more okay with this. As much as straight people demand that we do not change their sexuality, I wish that they would also pass on that safe humanity to LGBT people. Don’t change us, we are not trying to change you either.

I have also written a book together with Nagarajan, Chitra, Aliyu, Rafeeat, and it is called: She called me woman and it has really cool stories of the lives and realities of LGBT people who live in Nigeria.

There’s the story of a trans one. In fact, the name of the book, She Called Me Woman is about this transwoman who said that the first person who called her a woman was her teacher at the University of Ibadan, even when she wasn’t ready to call herself a woman, she called her woman.

Where she had acceptance and protection from school authorities, where everybody knew what her gender identity was and as much as there was bullying, there was also support.

Where her family tried to take her to a psychiatrist and lock her up and see ways in which they would medicate her to stop her from identifying as a woman or dressing or projecting as a woman, instead what she met was support from the medical community. What ended up happening was people stepping in and teaching her family how to deal with gender dysphoria.

There are a ton of very interesting stories. There’s also heartbreaking stories of this man who tried to shoot his daughter because he found out that she was gay, at about 27 and he had always known all over that time, but he had hope that she stopped and was a good Christian girl.

She Called Me Woman is such a good place to start and there have also been books by for example Unoma Azuah, it is called Blessed Bodies and it’s the stories of so many queer LGBT.

There’s one of my favourite ones about this person who was very religious and is a gay man here in Lagos and every time he had sex with this man, he would say they should go down and pray immediately afterwards and that was a recurring theme.

There’s a couple of other books. Life Of Great Men by Frank Edozien, Fresh Water by Akwaeke Emezi. There’s a bunch of really great literature out there and also if you haven’t seen Ife that was done by Pamela Ife, it’s such a good story. It’s like thirty minutes long, but it packs a punch. It’s on the quality of TV and it’s one of my favourite movies that have been done in the past two years.

Also let’s not forget this award-winning book by Jude Dibia that was done in 2002, Walking with Shadows. It’s a true-life story of this man who lived in Lagos and was married to a woman.

They just turned it into a movie with Zainab Balogun and Ozzy Agu. He was a gay man but due to the heartbreak that happened in his life, he found this woman, who he got really friendly with and they agreed to marry. They married, had a daughter and led a wonderful life. He never looked back and never had a boyfriend.

One day, somebody started blackmailing him and sent all of this information to his wife which then led to various different things within the family. His nuclear family, his extended family and basically the choices that people in our lives make, the ones who chose him and said, “We don’t care, you’re still the same person.” and the ones who had decided that they were going to choose society over him. There’s really a ton of interesting, important, media work that has been going on in Nigeria since as early as 2002.

You have been an activist for a while, what has it cost you?

Well, I think it would be unfair to say no one is being public. We have a ton of public people who are LGBT in Nigeria for example we have Olumide Makanjuola who has been out, and a proud gay man in Nigeria all these while; you have Pamela Adie, who has been running a blog since early 1998 about what it means to be a woman from when she was married, to when she got divorced, to when she started leaving her life as an out lesbian. She also has a documentary called Under The Rainbow. If you check on Twitter, there’s someone called Amara the Lesbian. There’s also this person called Blaize who identified as non-binary.

There’s like a ton of out queer people in Lagos, Abuja, Calabar, Port Harcourt, Jos living their lives.

We take up space within the communications industry within the banking industry. So, yes, there are a lot of people who are out, who are leaving their lives.

Not all of them online, a lot of them you can see online, but I don’t think that I made any other sacrifices that any other activist has done in Nigeria. Environmental activists are losing their lives every day for standing up against oil spills or the cutting down of forests.

We have people who lost their lives here on the streets in Lagos during the EndSARS protest which the government continues to claim is a lie. We have people who lost their lives, for example in 2012 during the Occupy Nigeria protest. We still don’t have names for all of them.

We have so many gender rights activists who continue to be attacked and killed because of the rights that they stand for. So, activism itself in Nigeria is a very risky position, for lack of a better word.

We continue to take those risks because we believe that we can have a better life collectively as Nigerians, that we deserve more and that some people have to speak up. I really don’t think that I’ve made any more sacrifices than the various ones who have also been imprisoned and are being kept behind bars because they broke some laws in various state governments.

Well, you shouldn’t invalidate your own sacrifices…

To be honest, if I’m being 100% honest, I don’t think I have made any significant sacrifice as an LGBT activist in Nigeria. That’s partly because I have the privilege of class. I belong to an upward class of Nigeria. I am financially well off. So, all of the various sacrifices that I would have had to make have not been something that has been enforced on me.

I live in relative comfort, which is security I get also from my family name and all of that. I am educated and I’m also a lawyer. So all of these things stand in the way of most of the things that would be problematic for queer people.

For most queer people, we get harassed on the streets for either looking too masculine or effeminate. If you have a car, it means that you have reduced all of those hardships that are likely to come your way. When it comes to police harassment and arrest, the fact I even speak with a non-Nigerian accent goes a long way in protecting me, the people I know and the fact that I can pay my way out of most harassments also goes a long way in protecting me.

The fact that I have an education that I’m an activist, that my parents support me. I have family supports, I have friendships, all of these things stand in the way of thousands of discrimination to which would have been my reality as a queer person.

So, I’m grateful for it and I continue to find ways in which I can use my privilege to shift the power to pressing issues and the fact that everybody deserves to live as freely as and as comfortably as I’m able to in Nigeria, despite being part of the LGBT community. I think the only sacrifice I made was a lack of privacy because as you can see, a ton of my life is online. That’s the only thing and that I’m able to trade for people’s safety.

What ways can the country, corporate bodies, make the LGBTQ+ community safe?

Somebody asked me this week, what are the needs of trans people in Nigeria? And I feel like the needs of trans people, the needs of LGBT people are the needs of every Nigerian. The things that we want are not any different from others.

We want access to good healthcare. We want access to education. We want access to safety and where our rights have been trampled on, we want justice. We want access to be able to do a good job, to not be thrown out of our houses and things that we’ve worked for.

We want protection from the law, not to be picked out and singled out and discriminated against on the basis of our sexuality.

We literally just want to be left alone to exist, with the right that has been given to every single Nigerian inside the constitution, but most especially in Chapter 4 and in Chapter 2. We’re not asking for anything special, nothing different. We’re saying treat us equally as you would any other Nigerian who was born today and if you go like that, we would all be perfect.

What’s your biggest win in life?

My biggest win in life is finding myself. Finding myself has to be the biggest win. I used to be a full covering hijabite, who knew very early on that despite the fact that I was queer, that I had to live my life and be a good Muslim girl and marry and have kids and all of that, but when I found myself, I was able to allow myself and explore all the things that I could be and eventually I was like “I don’t want to be a lawyer, I want to work in human and women rights. Eventually, I was like, “I don’t want to do that. I want to work in technology and use various languages and work within the tech sector” and now I can work on digital security for various organisations. So finding myself has allowed me to be so much more.

How did you discover you were queer … I know you might wonder how I discovered I was straight too

You need to be able to listen to your intuition, to respect and honour your needs and the things that your body and your soul asks for. For some people, it means a higher calling into religion. For other people, it means leaving their truths and sometimes, many of us require therapy to be able to get to a point where we can trust ourselves, trust our bodies, trust our wants and our needs.

Other times we require an aha moment, where something we’ve always wanted, but we haven’t allowed ourselves to even dream about or society and the reality that we live has not allowed us the possibility of even achieving those dreams.

Part of finding yourself is truly shedding society’s expectations and coming back to yourself and asking what is my truth? What do I need? What do I want? And then honouring them and finding ways with which you can bring them to life.

There are so many people who are presently, probably married, trying to have kids. It’s what is expected of them, but half of them don’t even want it. It’s to be able to be honest with yourself and the people in your life and say “this is my reality, what is yours?”

Do you know what your truth is? So that way, we can find common pathways to build our lives together and I don’t think enough of that is happening. Many people are going by what is expected of them instead of what they actually want.

Do you have any life regrets?

I must. I do. I feel one of my biggest regrets was not leaving the practice of law early enough. It was such a heartbreaking profession that did so much harm and damage to me and I am happy I have left it.

As most lawyers, who are no longer practising it will say, we are now recovering lawyers. We are in the process of recovery. It’s a journey. It’s one of the big regrets that I have.

A second regret I think I have was living a life of lie for as long as I did. Just pretending and denying my reality for so long. It meant that I didn’t have honest friendships for a while and I pretended to be who I wasn’t for too long.

Currently, there was one girl. I don’t know, about two, three years ago. I think it was in 2017, whom I borrowed three million.

Up till now, she hasn’t paid back. I will catch her. It was one of my biggest regrets, trusting people. People are like why did you do that but she had a sob story about how every man she asked for investment wanted to sleep with her and the feminist in me was like we have to help women, we have to support women’s business.

Waiting for me to give her money, she went around doing what not she said she would. She was just spending my money anyhow and then after she finished, she disappeared. Changed her number, changed homes. I will still find her. One of my biggest regrets.

What’s the challenge with the legal profession?

Nigeria is not a place that builds a good practice of law and law is all about the practice and the practice of law is very disheartening. The process of it is heartbreaking, especially for young lawyers.

First of all, most people go to school for four years. Law students are already going to school for five years, that’s minus the ASUU strike, so you’re already behind your mates. And then you have to spend another exorbitant amount of money for one more year in law school. Then after that, before you can serve. So you’re three years behind all of your peers.

Then you’ll come to the labour market. People will start offering you forty thousand, fifty thousand, for all of these experiences and education you’ve acquired. Even some of the best paying law firms probably pay N120,000 outside of Lagos, Abuja, or Port Harcourt.

Even within these spaces that I’m calling, these big capitals, sometimes what they offer is fifty thousand and you work from 7 am until like 6 pm and it’s almost like slavery. You’re expected to do so much for so little pay and it’s a thankless job and it’s so thin at the top. It’s so impossible to get there. You already have to be from a wealthy household to be able to practice law properly, because who’s going to set up your office. Who’s going to buy all the books that you need?

If you go and you don’t have a car, everyone will call you charge and bail. They will look at you from head to toe and say I don’t want this lawyer, he doesn’t know what he’s doing.

Just like his legs are probably dusty because he took along or he probably had to get to where he got to in a bus. If you’re poorer or if you’re not as well to do. You don’t have your car, you’re most likely to be late for meetings, appointments because you’re relying on Lagos traffic. You don’t know as many people at the top that’ll open doors for you just to be able to get things done really quickly in Nigeria because there are so many holes.

So the practice of law is really heartbreaking and it’s not the fault of lawyers but the people who are at the top of the profession. They don’t seem to look down at the things that are genuinely needed by lawyers and it’s so heartbreaking because it’s such a wonderful profession and so many young kids want to be part of the legal profession. It’s just that after they become lawyers, the practice of law becomes non-viable for them. So, we have a ton of lawyers who are not legal practitioners.

For lawyers trying to make the switch to tech like you, what’s the template to make a seamless transition?

There’s actually a part of it that is super easy to get into. What do you call it? One of my mentors, Barrister Israel Usman works in Abuja. He’s been working in this field, basically on policies that have to do with the technological sector in Nigeria and that is a super successful field with people who still want to practice law. But also, tech right now is such a diverse field that is easy for anybody to get to.

You can take a six months intensive course and learn various languages. It can be C++, PHP. It can be CSL. It could be JAVA. It could be so many other things and do what it is you want to do. You could want to be, for example, an auditor and work in photography or you could want to build websites, or you could want to build mobile apps or you could even be at the business end of it by selling products and understanding the law and licensing. So there are many different parts. Having a law degree also helps with that because we are learned, we are the masters of all. We already have one step forward.

So, I always tell people, follow your passion and if you are thinking of changing, there are so many free courses on YouTube, there are also intensive paid courses in almost every city in Nigeria.

So just take advantage of it, it completely changes your worldview and it changes your earnings significantly. I have some friends who went to a boot camp for six months in 2020. Now, they already have a job, earning 5000 dollars a month. So, it’s a worthy investment.