Breaking News

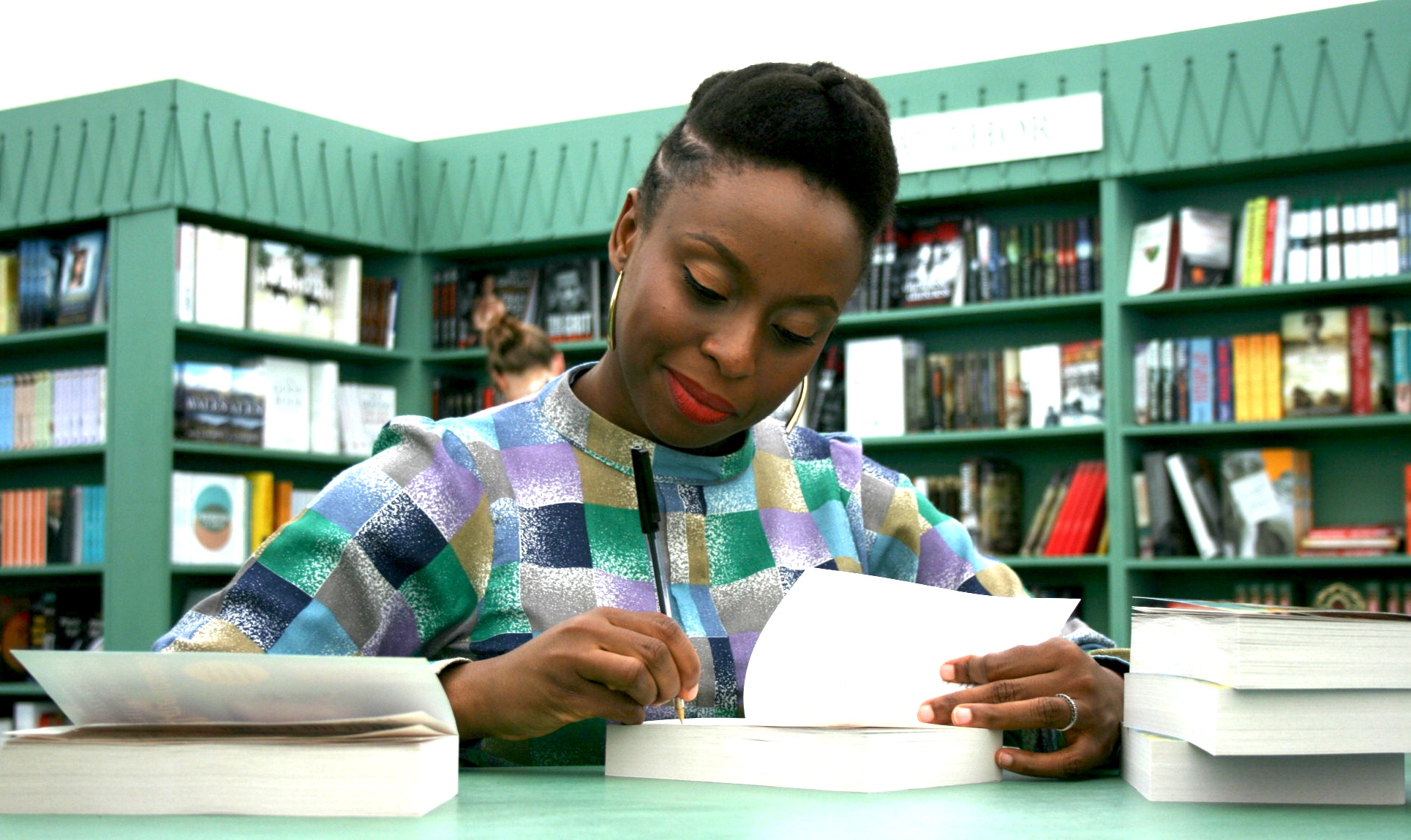

‘I Felt Violated, It Felt Like A Horrible Violation’ Chimamanda Adichie Talks About The Published Guardian Article On Depression

Nigerian author, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie in an Exclusive Interview speaks with Olisa Adibua and we culled excerpts of the conversation mainly about the published article the Guardian UK eventually took down, she tells of what really happened.

Enjoy…

A few weeks ago, the UK Guardian published an article online that you wrote about depression. Then a day later the article was removed. Many people were confused about this. There was much speculation. Some people even suggested that you might not have been the author of the article. I’d like for you to talk about depression and the story surrounding that article; why was it removed?

I was certainly the author. I have actually always been quite open about having depression. By depression, I don’t mean being sad. I mean a health condition that comes from time to time and has different symptoms and is very debilitating. I’ve mentioned it publicly in the past, but I have always wanted to write about it. I was meeting many people who I could tell were also depressive, and I was noticing how hush-hush it all was, how there was often a veil of silence over it, and I think the terrible consequence of silence is shame.

Depression is difficult. It is difficult to experience, difficult to write about, difficult to be open about. But I wanted to do it. For myself, in a way, because it forced me to tell myself my own story, which can be helpful. But also for other possible sufferers, especially fellow Africans, because there is something very powerful about knowing that you are not alone, and that what happens to you also happens to other people.

Depression is something I have recognized since I was a child. It is something I have accepted. It is something I will have to find ways to manage for the rest of my life. Many creative people have depression. I wonder if I would be so drawn to storytelling if I were not also a person who suffers from depression.

But I am very interested in de-mystifying it. Young creative people, especially on our continent, have enough to deal with without thinking – as I did for so long – that something is fundamentally wrong with feeling this strange thing from time to time. Our African societies are not very knowledgeable or open or supportive about depression. People who don’t have depression have a lot of difficulty understanding it, but people who have it are also often befuddled by it.

I wanted to make sure I was emotionally ready to write the piece. I don’t usually write about myself and certainly not very personally. I wanted it to be honest and true. The only way to write about a subject like that is to be honest.

Last year, a major magazine that I admire asked me to write a personal piece for them. I decided to use that as a prodding to finally write about depression. They liked the piece and were keen to publish it. They suggested some edits, and at some point I began to feel that the article was being made to follow a script, and that its integrity was being compromised. So I withdrew the piece. This was the most personal thing I have ever written and I felt it had to be in the form that felt most true. My agent then said that the UK Guardian was launching a new section that was supposed to publish long, serious pieces. She sent it to them and they were interested. But I had already begun to re-think the piece itself. I was no longer sure I was ready for it to be published. I thought about changing the structure. To make it two essays, one about women’s premenstrual issues and one about depression, so as to be more effective as a kind of advocacy memoir. Most of all, I decided I was not emotionally ready to have the piece out in the world. I wanted first to finish the new writing and research I was doing. So a day after my agent told me that the UK Guardian wanted it, I told her to please withdraw the piece completely. That I no longer wanted it to be published. The Guardian told her they were sorry I was withdrawing, but they understood. I didn’t think about it after that. My plan was – put it away, go back to it in a year, and see how I feel and revise and edit it.

This happened in September 2014. Then a few weeks ago, I was travelling and I get off a plane, turn on my phone, and see messages from acquaintances telling me how ‘brave’ I was. I was astonished. I had just written a piece for THE NEW YORK TIMES about my issues with light in Lagos and so I thought ‘haba, since when is writing about light brave?’

Do you remember what your first reaction was when you saw that an article you decided not to publish had suddenly appeared in public?

I felt violated. It felt like a horrible violation. This was the most personal piece I had written and the only person who deserved to decide when it would be read publicly was me.

Even their choice of words felt like a violation. They wrote that it was about my ‘struggling’ with depression. I would never have agreed to that caption. I do not think of the article as being about my ‘struggle’ with depression, but about my journey to accepting something I have had since I was born, and my choosing to ‘come out’ about it. I also hated that the sentence they highlighted from the whole piece was about how ‘the nights are dark…’ etc. It felt sensationalizing and cheap.

I was angry with the Guardian. Especially as their first apology was ‘we are obviously sorry.’ Any apology that contains the word ‘obviously’ is not an apology. They took it down and replaced it with an explanation about a ‘technical error,’ which even a child would have reason to doubt. It’s probably naïve of me but I had expected that they would be quick to admit their fault and make amends. There is something predatory about Big Journalism. Big Journalism doesn’t care about the humanity of it subjects. Big Journalism cares about ‘good copy’ and about not being sued. It took longer than it should have, but at least they subsequently published a proper explanation and apology, with the prodding of lawyers.

What did you make of The Guardian’s explanation that they had produced a ‘mock-up’ of the piece and then forgot to delete it in their system after you withdrew it and then it was automatically launched on their site? Also after it was taken down, many websites had already copied it and posted it, especially here in Nigeria.

I don’t understand how something stays on the website of a major, widely read newspaper for a whole day, something you have no right to publish, and nobody in your organization notices. As for the Nigerian websites, I think any website that puts it up is using what does not belong to them, which is called stealing. But this is the Internet age and of course I can’t really control any of that.

Well, I know for a fact that that article has been very widely-read and the consensus was that you were brave to write it and many people praised you. So I think it had positive impact.

I really hope other people who have depression found strength in it. My agent got many moving emails from people who were grateful that I had written about depression because they too had trouble even accepting that they had depression. I got responses from some distant friends and most were thoughtful and full of empathy and I was struck by how many said the piece made them feel better about acknowledging their own depression.

I also got a few responses that troubled me. Because I was generally quite upset by The Guardian, those responses further upset me.

William Styron who wrote the great novel Sophies Choice also wrote a memoir of depression, Darkness Visible, where he writes about being enraged by people patronising him and simplifying his depression to platitudes. I got a patronising email, for example, from an acquaintance which was full of passive-aggressive comments and then ended with ‘you are loved.’ And I thought: but that is obvious from the piece. I have a small solid circle of family and friends and I feel very loved and very grateful. But the piece is about the paradox of depression, that it is often a kind of sorrow without a cause. That being depressed makes even the sufferer feel bad and guilty because you are thinking of all these people you love and who love you and who you now feel strangely disconnected from. Another patronizing person told me ‘don’t worry, I won’t judge you.’ Which infuriated me beyond belief. Judge me? I didn’t know judgement was an option. Shame is not an option for me and never will be. Writing this piece was a choice I made. Being open about my vulnerability was a choice I made, and I don’t regret making it. There was also the usual Nigerian response of ‘just pray about it.’ I realized that many people who contacted my manager had either not understood the piece or had just read The Guardian’s choice caption of ‘nights are dark and I cry often’ and then decided to send me solutions ranging from bible quotes to various churches.

Did any of the responses really affect you?

I feel strongly, on principle, about the right to tell my own story. By publishing something I was not ready to publish, The Guardian violated that right, and I was very much affected by that. One particular response really saddened me. Someone asked my manager whether this was just a publicity stunt. I thought – have we become so soullessly cynical? Somebody actually thinks that if I wanted to pull a publicity stunt, I would write the most personal essay I have ever written about my own life?