World

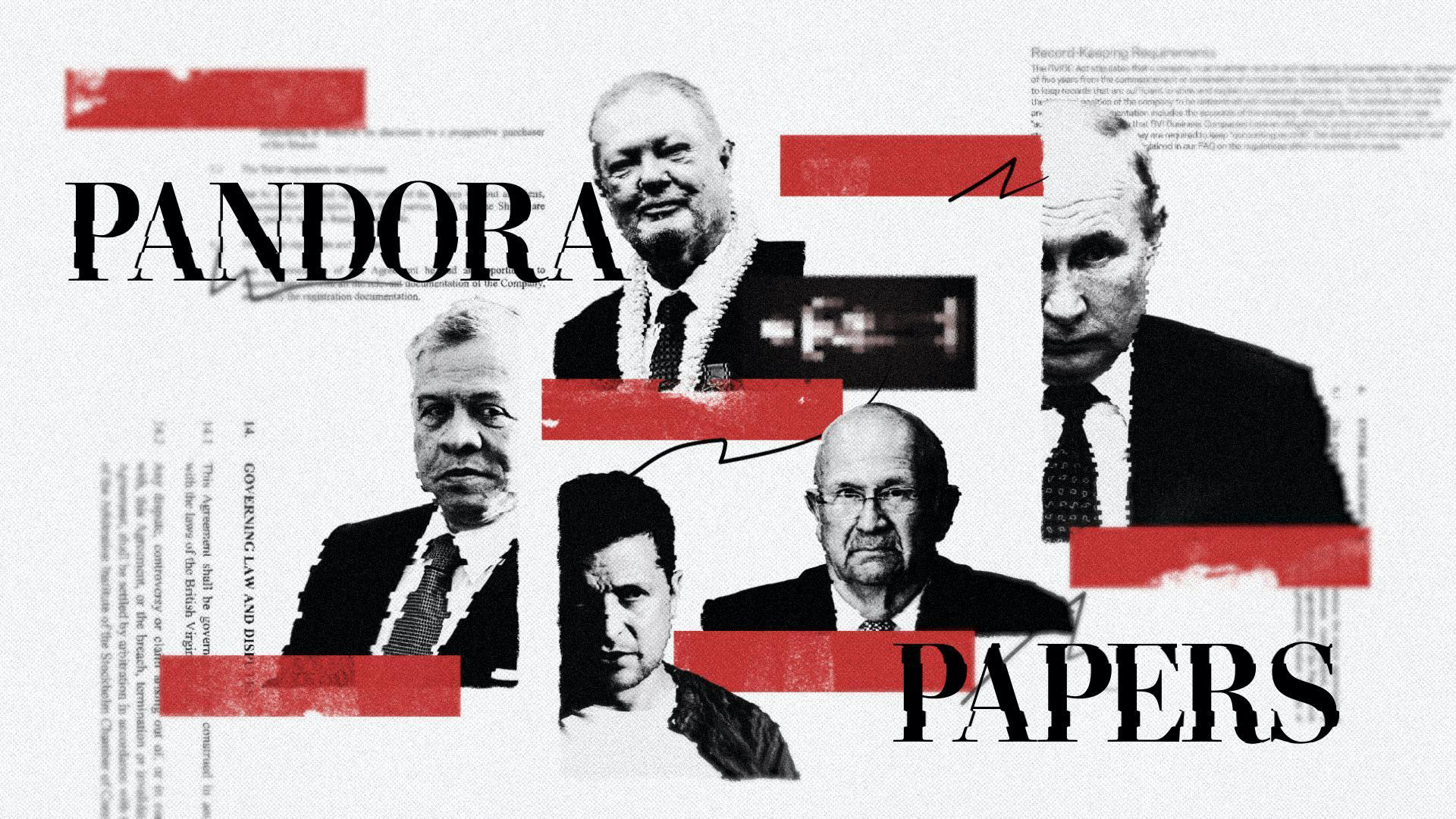

Pandora Papers: Offshore havens and hidden riches of world leaders and billionaires exposed

Millions of leaked documents and the biggest journalism partnership in history have uncovered financial secrets of 35 current and former world leaders, more than 330 politicians and public officials in 91 countries and territories, and a global lineup of fugitives, con artists and murderers.

The secret documents expose offshore dealings of the King of Jordan, the presidents of Ukraine, Kenya and Ecuador, the prime minister of the Czech Republic and former British Prime Minister Tony Blair. The files also detail financial activities of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s “unofficial minister of propaganda” and more than 130 billionaires from Russia, the United States, Turkey and other nations.

The leaked records reveal that many of the power players who could help bring an end to the offshore system instead benefit from it – stashing assets in covert companies and trusts while their governments do little to slow a global stream of illicit money that enriches criminals and impoverishes nations.

Among the hidden treasures revealed in the documents:

- A $22 million chateau in the French Riviera – replete with a cinema and two swimming pools – purchased through offshore companies by the Czech Republic’s populist prime minister, a billionaire who has railed against the corruption of economic and political elites.

- More than $13 million tucked in a secrecy-shaded trust in the Great Plains of the United States by a scion of one of Guatemala’s most powerful families, a dynasty that controls a soap and lipsticks conglomerate that’s been accused of harming workers and the earth.

- Three beachfront mansions in Malibu purchased through three offshore companies for $68 million by the King of Jordan in the years after Jordanians filled the streets during Arab Spring to protest joblessness and corruption.

The secret records are known as the Pandora Papers.

The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists obtained the trove of more than 11.9 million confidential files and led a team of more than 600 journalists from 150 news outlets that spent two years sifting through them, tracking down hard-to-find sources and digging into court records and other public documents from dozens of countries.

The leaked records come from 14 offshore services firms from around the world that set up shell companies and other offshore nooks for clients often seeking to keep their financial activities in the shadows. The records include information about the dealings of nearly three times as many current and former country leaders as any previous leak of documents from offshore havens.

In an era of widening authoritarianism and inequality, the Pandora Papers investigation provides an unequaled perspective on how money and power operate in the 21st century – and how the rule of law has been bent and broken around the world by a system of financial secrecy enabled by the U.S. and other wealthy nations.

The findings by ICIJ and its media partners spotlight how deeply secretive finance has infiltrated global politics – and offer insights into why governments and global organizations have made little headway in ending offshore financial abuses.

An ICIJ analysis of the secret documents identified 956 companies in offshore havens tied to 336 high-level politicians and public officials, including country leaders, cabinet ministers, ambassadors and others. More than two-thirds of those companies were set up in the British Virgin Islands, a jurisdiction long known as a key cog in the offshore system.

At least $11.3 trillion is held “offshore,” according to a 2020 study by the Paris-based Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Because of the complexity and secrecy of the offshore system, it’s not possible to know how much of that wealth is tied to tax evasion and other crimes and how much of it involves funds that come from legitimate sources and have been reported to proper authorities.

Every corner of the world

The Pandora Papers investigation unmasks the covert owners of offshore companies, incognito bank accounts, private jets, yachts, mansions, even artworks by Picasso, Banksy and other masters – providing more information than what’s usually available to law enforcement agencies and cash-strapped governments.

People linked by the secret documents to offshore assets include India’s cricket superstar Sachin Tendulkar, pop music diva Shakira, supermodel Claudia Schiffer and an Italian mobster known as “Lell the Fat One.”

Every corner of the world

The Pandora Papers investigation unmasks the covert owners of offshore companies, incognito bank accounts, private jets, yachts, mansions, even artworks by Picasso, Banksy and other masters – providing more information than what’s usually available to law enforcement agencies and cash-strapped governments.

People linked by the secret documents to offshore assets include India’s cricket superstar Sachin Tendulkar, pop music diva Shakira, supermodel Claudia Schiffer and an Italian mobster known as “Lell the Fat One.”

The Pandora Papers show that an English accountant in Switzerland worked with lawyers in the British Virgin Islands to help Jordan’s monarch, King Abdullah II, secretly purchase 14 luxury homes, worth more than $106 million, in the U.S. and the U.K. The advisers helped him set up at least 36 shell companies from 1995 to 2017.

In 2017, the king bought a $23 million property overlooking a California surfing beach through a company in the BVI. The king paid extra to have another BVI company, owned by his Swiss wealth managers, act as the “nominee” director for the BVI company that bought the property.

In the offshore world, nominee directors are people or companies paid to front for whoever is really behind a company. Application forms sent to clients by Alcogal, the law firm working on the king’s behalf, say that the use of nominee directors helps “preserve privacy by avoiding the identity of the ultimate principal . . . being publicly accessible.”

In emails, offshore advisers used a code name for the king: “You know who.”

U.K. attorneys for the king said that he is not required to pay taxes under Jordanian law and that he has security and privacy reasons to hold property through offshore companies. They said the king has never misused public funds.

The attorneys also said that most of the companies and properties identified by ICIJ have no connection to the king or no longer exist, but declined to provide details.

Experts say that, as ruler of one of the Middle East’s poorest and most aid-dependent countries, the king has reasons to avoid flaunting his wealth.

“If the Jordanian monarch were to display his wealth more publicly, it wouldn’t only antagonize his people, it would piss off Western donors who have given him money,” Annelle Sheline, an expert on political authority in the Middle East, told ICIJ.

In neighboring Lebanon, where similar questions about wealth and poverty have been playing out, the Pandora Papers show top political and financial figures have also embraced offshore havens.

They include the current prime minister, Najib Mikati, and his predecessor, Hassan Diab, as well as Riad Salameh, the governor of Lebanon’s central bank, who is under investigation in France for alleged money laundering.

Marwan Kheireddine, Lebanon’s former minister of state and the chairman of Al Mawarid Bank, also appears in the secret files. In 2019, he scolded former parliamentary colleagues for inaction amid a dire economic crisis. Half the population was living in poverty, struggling to find food as grocers and bakeries closed.

“There is tax evasion and the government needs to address that,” Kheireddine said.

That same year, the Pandora Papers reveal, Kheireddine signed documents as owner of a BVI company that owns a $2 million yacht.

Al Mawarid Bank was one of many in the country that restricted customers’ U.S. dollar withdrawals to stem economic panic.

Wafaa Abou Hamdan, a 57-year-old widow, is among the regular Lebanese who remain angry at their country’s elites. Because of runaway inflation, her life savings plummeted from the equivalent of $60,000 to less than $5,000, she told Daraj, an ICIJ media partner.

“All my life’s efforts went in vain. I have been working continuously for the past three decades,” she said. “We are still struggling on a daily basis to maintain our living” while “the politicians and the bankers” have “all transferred and invested their money abroad.”

Kheireddine and Diab did not respond to requests for comment. In a written response, Salameh said he declares his assets and has complied with reporting obligations under Lebanese law. Mikati’s son, Maher, said it is common for people in Lebanon to use offshore companies “due to the easy process of incorporation” rather than a desire to evade taxes.

‘Coalition of the corrupt’

Imran Khan was elated when ICIJ’s Panama Papers investigation came out in April 2016.

“The leaks are God-sent,” the Pakistani politician and former cricket superstar said.

The Panama Papers revealed that the children of Pakistan’s prime minister at the time, Nawaz Sharif, had ties to offshore companies. This gave Khan an opening to hammer Sharif, his political rival, on what Khan described as the “coalition of the corrupt” ravaging Pakistan.

“It is disgusting the way money is plundered in the developing world from people who are already deprived of basic amenities: health, education, justice and employment,” Khan told ICIJ’s partner, The Guardian, in 2016. “This money is put into offshore accounts, or even western countries, western banks. The poor get poorer. Poor countries get poorer, and rich countries get richer. Offshore accounts protect these crooks.”

Ultimately, Pakistan’s top court removed Sharif from office as a result of an inquiry sparked by the Panama Papers. Khan swept in to replace him in the next national election.

ICIJ’s latest investigation, the Pandora Papers, brings renewed attention to the use of offshore companies by Pakistani political players. This time, the offshore holdings of people close to Khan are being disclosed, including his finance minister and a top financial backer.

The documents also show that Khan’s water resources minister, Chaudhry Moonis Elahi, contacted Asiaciti, an Singapore-based offshore services provider, in 2016 about setting up a trust to invest the profits from a family land deal that had been financed by what the lender later claimed was an illegal loan. The bank told Pakistani authorities that the loan had been approved due to the influence of Elahi’s father, a former deputy prime minister.

Asiaciti records say that Elahi backed off from putting money into a trust in Singapore after the provider told him it would report the details to Pakistani tax authorities.

Elahi did not respond to ICIJ’s requests for comment. Hours before the release of Pandora Papers stories, a family spokesman told ICIJ media partners that “misleading interpretations and data have been circulated in files for nefarious reasons.” The spokesman added that the family’s assets “are declared as per applicable law.”

Also today, a spokesperson for Khan told a press conference that if any of his ministers or advisors had offshore companies, “they will have to be held accountable.”

Other political figures have also spoken out against the offshore system while surrounded by appointees and other supporters who have assets stowed offshore. Some who have spoken out have used the system themselves.

“Every public servant’s assets must be declared publicly so that people can question and ask – what is legitimate?” Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta told the BBC in 2018. “If you can’t explain yourself, including myself, then I have a case to answer.”

The leaked records listed Kenyatta and his mother as beneficiaries of a secretive foundation in Panama. Other family members, including his brother and two sisters, own five offshore companies with assets worth more than $30 million, the records show.

Kenyatta and his family did not reply to requests for comment.

Czech Prime Minister Andrej Babis, one of his country’s richest men, rose to power promising to crack down on tax evasion and corruption. In 2011, as he became more involved in politics, Babis told voters that he wanted to create a country “where entrepreneurs will do business and will be happy to pay taxes.”

The leaked records show that, in 2009, Babis injected $22 million into a string of shell companies to buy a sprawling property, known as Chateau Bigaud, in a hilltop village in Mougins, France, near Cannes.

Babis has not disclosed the shell companies and the chateau in the asset declarations he’s required to file as a public official, according to documents obtained by ICIJ’s Czech partner, Investigace.cz. In 2018, a real estate conglomerate indirectly owned by Babis quietly bought the Monaco company that owned the chateau.

Babis didn’t respond to requests for comment.

A spokesman for the conglomerate told ICIJ that it complies with the law. He didn’t respond to questions about the acquisition of the chateau.

“Like any other business entity, we have the right to protect our trade secrets,” the spokesman wrote.

[Originally published on ICIJ]