Featured

The Feminist Coven and the Fight against Sexual Violence in Nigeria

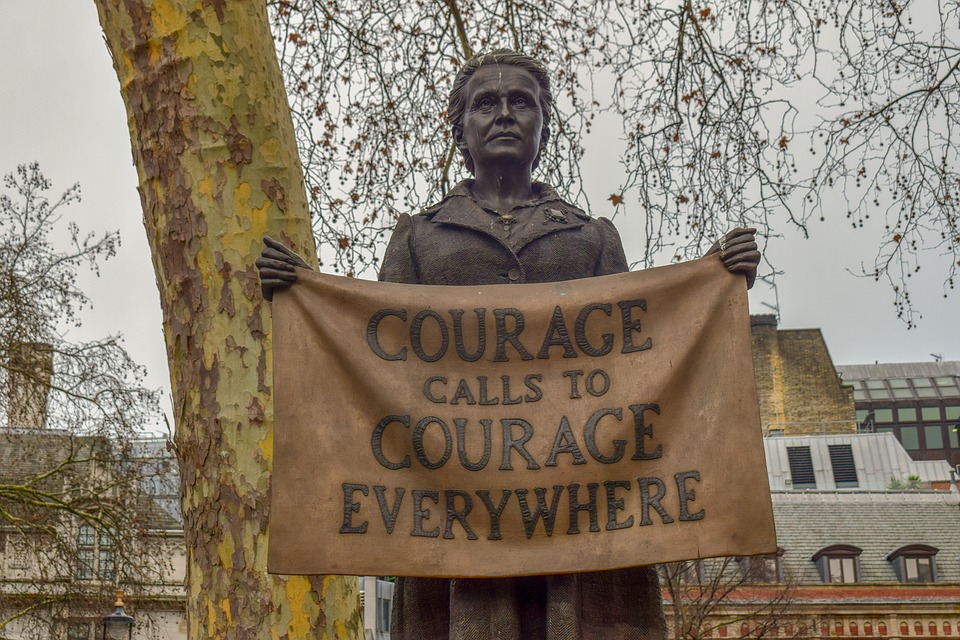

In a 2017 essay, Maggie Rosen argues that “the contemporary denigration of women politicians as witches is rooted in historical context.” If it wasn’t Margaret Thatcher, the Prime Minister of United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990, it was Julia Gillard, the 27th Prime Minister of Australia or Hillary Clinton, USA candidate in the 2008 and 2016 Presidential elections. From political spheres to the most mundane jobs, women have, for centuries, been referred to as witches. So, it was no surprise to learn that in Nigeria, the most outspoken group on social media – the feminists – have been labelled as a Coven for refusing to remain silent in the fight against sexual violence across the country.

Social media provides a platform for the voices of African women to be amplified in a way that our communities – which are primarily patriarchal and arguably misogynist – do not. Conversations about sexual violence are important in physical social spaces and they are also important on online, given the influence social media has had, and continues to have, on millennials.

Kiki Mordi, award-winning Nigerian journalist, media personality, filmmaker and writer told NewsWireNGR that social media is just a replication of our social space. She said: “It’s very important to have these conversations in real life; it’s also very important to have them on social media – to create awareness for people to be aware of their rights, their bodily autonomy and for people to be aware (and educated) of the implications of certain things.”

It was on social media that the popular #MeToo movement against sexual violence was birthed in 2006 by a New-York based advocate for women, Tarana Burke. With the movement, she hoped to “empower women who had endured sexual violence by letting them know that they were not alone – that other women had suffered the same experience they had.”

Over a decade later, in 2017, actress Alyssa Milano reintroduced the term in an attempt to encourage survivors of sexual violence to speak up. This time, it went viral and the movement was domesticated by countries and religious groups in an attempt to fight against sexual violence. In Nigeria, we have seen Muslim women participate in the #MosqueMeToo movement, which was initiated by Egyptian-American journalist and author Mona Eltahawy to encourage Muslim women to speak up against sexual harassment in religious spaces. We have also seen #ArewaMeToo kick off, reaching out to northern Nigerians to speak up against sexual abuse and harassment. In the same vein, hundreds of brave protesters assembled outside church premises, chanting anti-rape songs in the #ChurchToo movement, forcing the resignation of a popular Nigerian pastor, Biodun Fatoyinbo. These movements took off on social media and have played active roles in creating awareness about sexual violence and ensuring the safety of survivors after speaking up against their perpetrators.

Damilola Odufuwa, a staunch member of the feminist coven, believes that social media also has the ability to force the people in power to listen to the cries of civilians and take active steps towards implementing the necessary change. As the co-founder of Wine and Whine, a group that seeks to fight patriarchy and create a safe space for women in Lagos, she believes that online spaces can bring awareness to major problems faced in our societies. They provide a platform for conversations to be had and for movements such as #BlackLivesMatter and #BringBackOurGirls to be birthed and manifested in different communities across the globe.

“Social media often forces society to take a look at itself in the mirror,” Damilola told NewsWireNGR, explaining that creating awareness on social media can bring about the change needed in many communities.

Social media also emboldens women. Through the #MeToo movement, women have found the courage to speak up about being survivors of abuse and realize that they are not alone. For Damilola, through these thriving social media movements, it is obvious that there is power and impact in sisterhood. For Kiki, her social space is where she promotes her passions, especially gender equality. “I was never politically correct about my stance on gender inequality,” she said. “It was never something I was politically correct about.”

Kiki Mordi’s political incorrectness paved her journey to #SexForGrades documentary, the most successful domestication of the #MeToo movement in Nigeria. For this BBC Africa Eye investigation, undercover journalists were sent to the University of Lagos and the University of Ghana – while posing as students – to expose sexual harassment on campuses. The producers spoke to dozens of then-current and past female students of the universities to highlight the commonness of sexual violence in West African universities.

“Seeing yourself represented makes you realize you’re not alone and you are not powerless,” Damilola said. “Seeing other women speak out about their experiences validates yours.” It is how safe spaces are created, she said – with one woman standing up for another woman and ten women standing up for them; from one woman to ten to a community that serves as a safe space for women.

Netflix’s hit series, Sex Education, portrays this in a scene that has since been considered the most important TV moment. When Aimee (Aimee Lou Wood) gets sexually harassed on the bus on the way to school, she becomes terrified of getting on the bus and chooses to walk to school every day instead. The post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) also manifested in other ways – she starts seeing her assaulter’s face everywhere, which affects her life much more negatively that she wants to admit. Aimee finally breaks down in detention with the girls, talking about how bad it really is and the next day, the girls meet her at the bus stop and ride to school with her. Damilola feels that this scene is proof that women connecting over the trauma of sexual harassment helps make survivors feel safer and possibly heal faster.

This sisterhood doesn’t only exist in movies and TV shows; it exists on social media and in reality, too. “It’s important for women to know that they have spaces not just on paper [but also] in reality, in our body language,” Kiki Mordi said. She explains that women often feel alone, like there is no one on their side and also feel unsupported by legal and social institutions. “But it’s important to know that if the system won’t help you, women around you can protect you,” she adds.

The female protectors are often feminists or women who are strong advocates for women’s rights, who encourage survivors to speak out, to seek justice and to heal. In June 2020, news spread on social media that 12-year-old Farishina was raped by 11 men, one of whom was a 57-year-old man. In light of the event, Feyikemi Abudu and Jola Ayeye, the voices behind I Said What I Said, a podcast about millennial culture, raised over a million naira, which they used to fund the survivor’s education, healthcare services and to support her family.

On another instance, in 2018, a news analyst and filmmaker, Ireti Bakare-Yusuf, announced that she was creating an app called #NoName, which enables survivors to report cases of sexual violence in Nigerian universities.

In July 2020, the First lady of Kaduna state, Aisha Ummi Garba El-Rufai, led a group of protestors to the National Assembly to advocate for stricter punishments for perpetrators of rape and sexual harassment across the country. “It is unacceptable that a person who rapes is given seven years or twelve years,” she argued fervently. “The person should be locked, and the key thrown away.”

Individuals can and have done remarkable work to support victims. We also have non-government organizations (NGOs) at the frontline of this battle. “It is very important that the voices of these women are amplified,” Kiki told NewsWireNGR, explaining that these organizations remind survivors to fight the rape culture back. “We will not be deterred, and we definitely will provide survivors with unwavering support during these times,” she said.

Damilola is also a relentless supporter of women and organizations who are working tirelessly to bring an end to sexual violence. The works of such organizations have not been in vain. “My role is to amplify their work, help raise funds for their work and to create a community where the average woman has the access, education and confidence to also join in the fight,” she said.

There are many Nigerian organizations who are determined to help survivors of sexual violence across the country. Stand To End Rape (STER) is a youth-led movement which aims to end all forms of rape, provides psychosocial services and support for victims and educates people about rape; Women at Risk International Foundation (WARIF) provides victims with free medical and legal aid, as well as shelter and counselling; Hands Off Initiative teaches children, teenagers and adults about consent; The Mirabel Center also provides holistic and high quality medical and psychosocial services to survivors of sexual assault and rape. There are many other organizations including Sexual Offences Awareness and Response Initiative (SOAR) and Women’s Rights Advancement and Protection Alternative (WRAPA) that are fighting vigorously to bring an end to this epidemic.

Women have always stood up against injustice in Nigeria; we have all heard stories of Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, who dared to drive in a country where women were not allowed to drive and the thousands of women who came after her, pushing boundaries. While it is remarkable that women play crucial roles in the fight against sexual violence in Nigeria, it leaves the impression that rape and all other forms of sexual violations are crimes against feminism, not humanity. We live in a country where women bond over being survivors of sexual violence and a huge percentile of the female population has either survived such violation or knows someone who has or knows someone who knows someone.

It is a human rights issue and where governmental organizations fall short – listening to and believing survivors – the feminist coven provides a safe space for women to share their stories. Where many state governments have refused to domesticate acts that adequately punish perpetrators, the feminist coven raises funds for the legal fees of survivors and drag the perpetrators to court to seek justice. Where the police might accept hush money from perpetrators, the feminist coven ensures that survivors of sexual violence get support from the masses. The coven has done an amazing job creating awareness of sexual violence; the government needs to take this a step further to provide safe and equal rights to its citizens.

“The current norms benefit them,” Damilola told NewsWireNGR, describing why she does not believe the Nigerian government is ready to bring an end to sexual violence. “They are the gatekeepers and they protect powerful men and women who have committed such crimes.”

Her opinion is supported by the popular story of Senator Elisha Abbo, the Adamawa state representative, who was caught on camera assaulting a woman. The police closed the case, letting him walk a free man with no reparations. It can also be supported by the unlawful arrest of Seyitan Babatayo, after she opened up about being raped by popular music artist, D’Banj. If there are unwritten laws that ensure the subjugation of women and supports perpetrators of sexual violence, then we need new laws. As Kiki Mordi said, “the Nigerian government lacks the political will to bring sexual violence across the government to an end.”

Damilola agrees. “We need to change our laws, re-educate our law enforcement on these laws and also on their biases against women and ensure that there is effective punishment for those who break laws put in place to protect citizens,” she said, adding: “even if those who break the laws are the lawmakers themselves.”

Through continual conversations facilitated by feminists and activists against sexual violence, the coven has already done a remarkable job educating people about consent and changing the narrative around sexual violence. But NGOs can only go so far. Nigeria is in dire need of effective leadership for the constitution to change and for these conversations to have a long-term impact in our societies. Damilola hopes that a change in the constitution means rapists should be punished to the full extent of reformed laws.

Kiki Mordi agrees. She told NewsWireNGR that “to fight rape culture, we need structures that work.” The fight against sexual violence in Nigeria does not need superheroes; it needs feasible structures. Today, survivors of sexual violence cannot successfully report cases to the police, unless they arrive at the police station with an organization holding their hand or have gathered enough outrage on social media. Because Nigeria does not have a practicable structure, people have to go on social media to open up about intimate details; their lives are subsequently subjected to public opinion. Yet, this is still just rolling the dice; justice might still not work. We need feasible justice and criminal institutional systems to protect survivors of sexual violence across the country.

This is not to say that the Nigerian government has done absolutely nothing to stand against sexual violence. In 2015, the Violence Against Persons Prohibition (VAPP) Act – which prescribed severe punishments for perpetrators of sexual harassment, including a minimum of twelve years in prison, without the option of a fine – was introduced. However, five years later, 23 of Nigeria’s 36 states have still not passed the bill. In November 2019, during a standstill rally organized by North Normal – a Northern-based group that advocates for the domestication of the VAPP act across the country – the movement’s leader in Sokoto, Sadiya Taheer, was beaten and assaulted by almost 20 policemen.

In October 2019, Senator Ovie Omo-Agege, the Deputy President of the Senate, reintroduced the ‘Sexual Harassment in Tertiary Education Institution Prohibition’ bill. Three years earlier, he was part of the team that initiated it, criminalizing sexual relationship between university lecturers and students and prescribing a five-year jail term to lecturers found guilty of sexually harassing students. Yet at a public hearing, the Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU) stood firmly against the bill, claiming that it was a violation of the rights of the university lecturers. “The rights”, of course, includes sexually harassing students and promising and awarding them good grades in exchange for sex.

Just recently, the Senate passed a bill, prescribing a two-year jail term for teachers found guilty of sexually harassing their students. While this should be seen as a step in the right direction, they are ambling when they could – and should – be moving more swiftly and effectively. A two-year jail term does little to change the mind of an abuser; the country will benefit much more should the 36 states domesticate Kaduna’s death penalty for rapists.

At the moment, it seems as though NGOs care more about sexual violence than governmental organizations. However, they are widely underfunded and while relatively influential on social media, they do not have access to resources governments do, leaving them disadvantaged. “Government should try as much as they can to collaborate with organisations that have done a lot of legwork,” Kiki told NewsWireNGR. These organizations have already conducted research into these topics but do not have enough resources to implement the necessary changes. “The government can meet us halfway – speak to organizations and implement changes,” she adds. “If you really care about women and you want to help them, you would listen to women.”

In 2018, architect Damilola Marcus launched Market March to de-normalize sexual harassment in Nigerian markets so as to make it a more hospitable environment for women to shop without the fear of being stroked, grabbed, groped or harassed without their consent. On the day of their first petition at Yaba market, which is infamous for sexual harassment, it was reported that “Yaba” was one of the trending topics on social media, with thousands of supporters. Market March also called upon people to sign a petition for the implementation of the sexual harassment law. It calls for the creation of an ‘Anti-Sexual Harassment and Bullying’ Police Squad, while the organizers took it upon themselves to teach traders about boundaries and the consequences of their actions on women, as well as their sales. State and federal governments supporting movements like this can go a long way in ensuring that people are well-educated about sexual harassment and in the event that they choose to violate women, there are severe consequences.

Kiki believes that it is possible to change the attitude towards sexual violence with or without the help of the government; but with their involvement, it would be more constitutional and more systemic. “The government’s job is to protect its people and if that excludes women – a huge percentage of its population – then you’re not protecting your people,” she said. She argues for laws that protect women; instead of leaving NGOs and feminists to teach boys not to rape women, stricter punishments should be put in place to put an end to rape. “The society shouldn’t have to endure changing this huge, attitudinal change towards rape culture; we shouldn’t have to endure it without the help of the government,” she said.

It is important to have laws that protect women because we live in a world where we are not safe. Statistics have shown that 1 in 4 women have experienced rape or attempted rape during their lifetime; almost 80 percent of rape survivors did not receive medical attention after the incident; almost 60 percent of undergraduate women experience harassment while enrolled in college; more than one-third of women who report being raped before the age of 18 also experience rape as an adult; and in a study of elderly female victims of sexual abuse, 81 percent of abuse was perpetrated by the victim’s primary caregiver, 78 percent was perpetrated by family members, of whom 39 percent were sons.

“Sometimes, my role is simply to hold hands of people, so they don’t feel alone. Other times, my role is being a network,” Kiki said. When she is unable to help survivors of sexual violence, she helps them access counsel and safety. Through her network, she is able to help them find the help they need, or someone who knows someone who knows someone who can help.

‘Coven of feminists’ was a term coined to degrade and silence women who take to social media to take a stance against issues such as sexual violence. However, it has since been reclaimed by the women in question, with many of them selling merchandise and capitalizing on the label. “Branding outspoken women as witches is something men have done for centuries to shame women and incite violence against women,” Damilola said. “For me, it has only encouraged me to speak out more and support my future feminists.” She believes there is strength in numbers and that this generation of women has proved time and time again that they will not be shamed into silence. She hopes for a future where the feminist coven is full of recognition, protection and support, where the works and talents – as well as the contribution and importance – of the feminist coven is realized and amplified in the society.

Damilola wants a future that is fair and just to women. For that to happen, everyone has a role to play. Civilians need to vote to put the right people in power, donate to NGOs and volunteer with them to encourage them, demand legislative reform and stop injustice by rebuking patriarchal norms. Governments need to do their job; they need to listen to marginalized citizens, create and enforce laws that protect them. NGOs just need to keep up the good work.

For Kiki, she just hopes that the future means “women wouldn’t have to fight half as much as we do now.” It means justice and reforms; it means bodily autonomy; it means freedom. And if that freedom comes with a “witch” tag, then the future also holds an unbreakable assemblage of feminist covens.