Opinion

Wole Olabanjo: (Rejoinder) Why Does Northern Nigeria Have An Economic Problem?

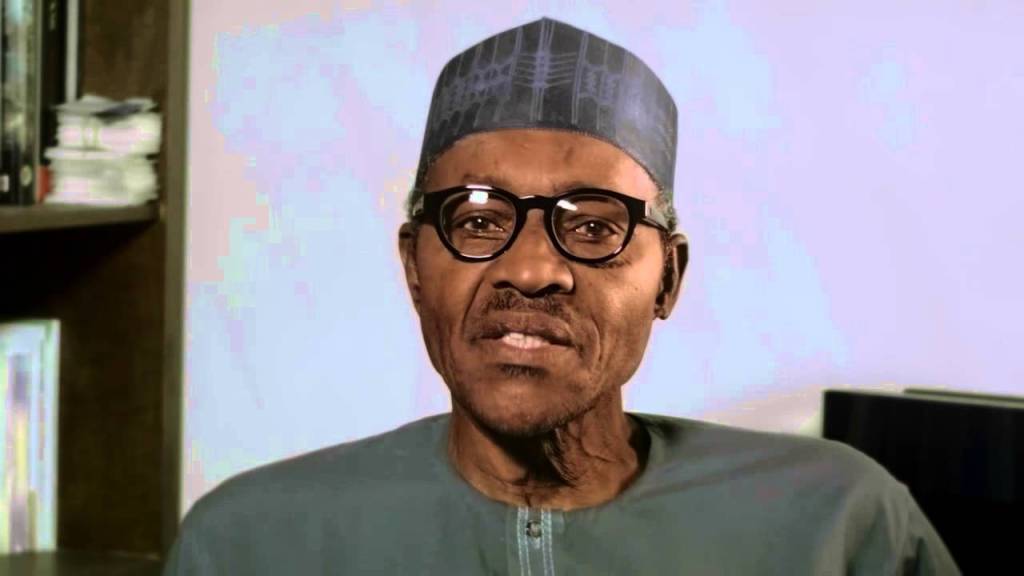

Tahir Sherrif (@tahirsheriff) in this article raises the important question of whether Muhammadu Buhari, if elected president will be able to “end the economic slavery of northern youths”. His intervention aims rightly to set agenda for a candidate who many consider may have a fair shot at winning the 2015 presidential race.

While Tahir stays characteristically objective, I feel that perhaps the key assumption that forms the basis of his intervention does not burrow deep enough into the problem as to help us gain a fuller picture of the situation in the north. Like many other people who have weighed in on the insurgency problem in the north, he seems to have relied rather too heavily on the thesis that the nature of the problem is essentially economic.

To quote him… “Some have blamed Islam for the economic state in northern Nigeria, this is sad, but using beer-parlour analysis, what other explanation is sufficient. For a lot of Nigerians, especially those who reside permanently in the southern parts, what else could doom a man into strapping himself with explosives if not his beliefs? Some have blamed the puritanical Fatwa’s by Mallams in the region; fanatical men who preach destructive doctrines creamed with promises of heaven and seventy-two virgins. But some the educated northerners themselves can see the problem for what it is; an economic one. What is most obvious for those who were born in the north, have lived a significant number of years there, and have travelled to almost every corner in the northern states, the uniform explanation is that people there simply have nothing to do.”

Although I am of the opinion that this statement is factual, I think that it falls somewhat short of identifying a more important root cause, and thereby hinders us as a society from easily recognizing the more effective courses of action open to us. Nevertheless, I believe his intervention offers us another opportunity to have a wider discussion of the subject and perhaps take the first steps towards turning the corner.

The more important question

While economic exclusion, and the attendant poverty is undoubtedly a significant factor in the emergence and growth of insurgent ideologies, is it not perhaps true that the more important question that this raises is “why is the north excluded and poor?” A useful analogy that aids understanding can be found in the treatment of Immuno-deficiency Syndromes. While specific infections can be the immediate causes of sickness, what we now know of those diseases indicate to us that the more sustainable way of managing them is to pay serious attention to the problem that originally compromised the immunity of the patient.

In other words, the angle to consider is that, “economic exclusion is just a symptom of a deeper problem”, and that the more sustainable way to approach a solution is to have a broader, long term strategic plan with clear and implementable policies. Hitherto, the predominant approach (one balks at describing it as strategy) has been to create a short-term, subsistence and ‘unscalable’ economy which runs on the wheels of barrows powered by human sweat.

Tahir offers a useful anecdote in understanding the lid on the human potential that is keeping the north notoriously backward. “Northern Nigeria” he writes, “is a region where you can see a Kolanut seller sit under the sun for a whole day, leaving his tiny tray of kolanut only during pray(er) time, and returning home later on to his two wives and five children.”

Not only is this anecdote true, it is actually rampant. There are far too many people in northern Nigeria who are trapped in similar, chronically unsustainable businesses. This creates what is essentially a regional economic model powered disproportionately by sweat. So when Tahir writes of the “economic slavery of the north”, it actually invokes the idea that the north’s economic model is as outdated as and similar to slavery; relying as it does nearly exclusively on brawn, and to the exclusion of brain.

What is wrong with the brain of the northerner?

Absolutely nothing! Having lived in northern Nigeria nearly all my life, I have of course met a fair number of brilliant northerners. For instance, I have many Hausa/Fulani friends from secondary school who were just as bright as any of the other students from other parts of the country (I went to a Federal Government College that had students from every corner of Nigeria). Shamsudeen Yabo for instance had a reputation for having a photographic memory. He would attend class and that was enough to pass all exams. He is about now wrapping up a PhD in Chemical Engineering in the UK. Nasiru Hayatu was the skinny, geeky Fulani boy who the last time I met was a top engineer in one of the Telcos. More noteworthy, there was G9.

I vaguely remember his full name as Mohammed Lawal or so, but I can’t ever forget his nickname. G9 was about 19 when he joined us in JSS 1. He was a Fulani guy who we were told had only attended some nomadic school. My principal, A.B. Yawa picked him up from somewhere, adopted him and enrolled him in first year with us. Of course his grammar was appalling in the beginning, but by the time we were finishing 6 years later, it was vastly improved and as far as I can remember, he managed to cope with the academic rigour.

In reality, it is unnecessary to mention personal encounters to prove that the northerner has the same physiology and by extension innate capacity as any other human being. Obviously, the difference between the north and south in terms of educational accomplishment arises from variance in socialization. Somehow, northern Nigeria lies at a unique intersection of faith, culture and geography which I believe has predisposed the region to develop a worldview that takes a dim view of formal education. This in turn sets off a chain reaction of very debilitating social conditions.

Let us revisit Tahir’s Kolanut seller; shall we call him Mallam Ali? To understand the policy challenges that confront the northern region, it is critical to gain insight into why someone like Mallam Ali would assume that he can support two wives and five children (I think 7 children is closer to the mean) on income from a business with inventory that can fit in a small tray. Or if like Tahir says “even this Kolanut seller wishes to do things differently”; why he is unable to muster the will or find a way out of his obvious quagmire.

Fundamentally, what Tahir describes as contentment in reference to Mallam Ali is in reality probably fatalism. In the admirable equanimity with which the northerner takes almost every event, a closer look might also reveal a pitiable resignation to fate. Many a northerner views reality as the unfolding of a series of predetermined events over which he has no power. Such a mindset clearly aborts aspiration and paralyses the will; keeping folks like Mallam Ali ‘contented’ with his tray of kola nuts and the lot that it can afford him in this life.

The Education Factor

While I know of no specific studies, my personal observations over a couple of decades and scores of cases incontrovertibly establishes that the more educated a northerner is, the smaller the size of his family is likely to be. Educated northerners who are Muslims are more likely to have one wife; she in turn is more likely to have fewer children than those who are not educated.

This ‘education’ factor is at the crux of the unemployment and insurgency problems that we see in the north today. The overwhelming majority of those who are unemployed or involved in the insurgency are teenagers and young adults who have had too little or no schooling to be able to function in a formal economy. Furthermore, they are typically without any artisanal skills that are of any real value in the semi-formal and informal economies. In the most, all they have to offer is raw energy for the lowest forms of unskilled labour.

They are typically the spill overs and left behinds from the brimming families of the likes of Mallam Ali the Kola nut seller. Hardly ever the children of people like my friends from secondary school: theirs more than likely will go to decent private schools and end up in the formal economy.

For many in Nigeria, when they come across news headlines like “There are 10 million out of School Children in Northern Nigeria”, it just sounds like particularly appalling data. For those who have had a closer, one-on-one interaction with this problem as I have however, the connection with emerging realities like Boko Haram is unmistakable.

To illustrate: for some reason, eclipses of the moon seemed to be a particularly common occurrence in the eighties when I was growing up in Zaria. On those nights when there was an eclipse, a flash mob of street kids would suddenly appear and roam the streets chanting menacingly in Arabic “there is only one God and Mohammed is his prophet”, while hurling stones at houses of ‘foreigners’.

These experiences I describe were of course only one type of the many in which these kids poured unprovoked into the street to terrorise people. Anyone who takes an objective view can see the ideological and socio-cultural streak that connects those kids and Boko Haram.

Importantly, except for very rare exceptions, these terrifying mobs comprised entirely of out of school teenagers and young adults who were abandoned by their parents in the many local Almajiri schools in the town. Hardly ever would you find children of educated people going round hurling stones at people simply because there was an eclipse of the moon.

A Clash of Cultures

If there was one single policy direction that could have the greatest impact on reinventing northern Nigeria, it would definitely be raising literacy levels. This of course raises the question of whether key policy shapers in the region are aware of this. My guess would be “yes”. That might then imply an allegation that leaders in the north are either lacking in will or deliberately sabotaging their own progress. I would answer that the situation is probably a bit more nuanced.

While Boko Haram’s complete repudiation of education (they qualify it as western education) is clearly an extreme view, there is undoubtedly a widespread tension between education (and how it shapes culture) and Hausa/Islamic culture that is dominant in the north.

The truth is that education which is dominated by the spirit of scientific inquiry tends almost unequivocally to create prosperity and a liberal culture. Understandably, because the west mostly took the lead in pursuing this form of education, and subsequently experienced the prosperity and liberalization it births, liberalism is today adduced to the west rather than more appropriately viewed as an inevitable outcome of an education system dominated by the scientific worldview.

However, lured by prosperity, many high context and/or religious cultures who have sought to pursue an education system that is disproportionately shaped by the scientific world view invariably experience this tension. Examples abound; the Gulf States, Turkey and China for instance continue to struggle with moderating the rise of liberalism but it increasingly appears to be merely a matter of when not if.

Closer home, a sampling of educated northerners will show that liberal attitudes are far more dominant in this group. Some of it is just because of better knowledge: educated people for instance are less likely to believe the conspiracy theories that are rife in northern Nigeria about polio vaccines and therefore vaccinate their children. The corollary is however that they also tend to be more at home with western cultural totems (e.g. cloths, handshakes with women etc.) that may be deemed incompatible with their religious beliefs or even outrightly sinful.

In the context of such realities, it is understandable that policy shapers (especially those with strong Islamic religious beliefs) in the north may be wary of a wholesale and aggressive education of their citizens.

Although there is a real and understandable feeling that education threatens identity and a cherished cultural heritage. Leaders in the north need to realize that the greater threat is the lid that illiteracy places on human potential. An illiterate population invariably develops a set of tendencies that ultimately results in a conflict ridden society. They reproduce unsustainably, creating a youth bulge that is restive, and produce inefficiently resulting in very high levels of poverty. This scenario is tinder for the match of a society with a surplus of superstition and shortage of reason.

Reinventing the North

A lot has been said about agriculture and solid minerals being the two-prong approach to developing the economy of northern Nigeria. While these are clearly important components of the required strategic framework, education is in reality the most important component. Increasing incomes for an illiterate population can actually have the counterproductive impact of fuelling some of the negative cultural choices that brought us where we are today.

For whoever wins the coming election, the most important thing to pursue towards building sustainable peace and a vibrant economy in Northern Nigeria is an aggressive policy of educating the Northern population. Essentially, there needs to be a ‘marshal plan’ for drastically cutting illiteracy levels to the barest minimum in no more than 20 years.

One aspect of this policy should be an honest evaluation of the impact of affirmative action in raising literacy levels in the north. Clearly, having an open ended policy of discriminatory admission standards can only be counterproductive in the long term. What needs to happen is a gradual raising of the bar; over say a 15-year period after which all Nigerians from all parts of the country will be required to meet uniform requirements for admission into institutions.

Of course, no one has to surrender their cultural heritage in order to get an education that allows them be functional citizens in an increasingly globalized economy. What needs to happen is that the education policy should be designed in such a way as to acknowledge and as much as is necessary embrace local realities.

The alternative is a northern Nigeria where Boko Haram and its destructive theology leaves the fringes and establishes itself in the geographic and ideological core of society.

______________________________________

Article written by Wole Olabanji @woleolabanji

Disclaimer

It is the policy of NewsWireNGR not to endorse or oppose any opinion expressed by a User or Content provided by a User, Contributor, or other independent party.

Opinion pieces and contributions are the opinions of the writers only and do not represent the opinions of NewsWireNGR.