Opinion

Opinion: Between Rigasa Schools And The Kaduna State Government

By Zainab Sandah

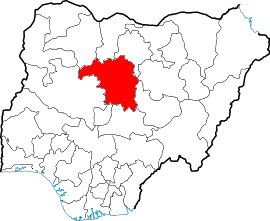

In the first quarter of 2013, I surveyed and collected data across 7 public primary schools in Rigasa, a densely populated ward under Igabi LGA in Kaduna State with the objectives of: generating a report capable of guiding policy formulation and implementation for the rehabilitation of education facilities/infrastructure and raising standard of education within the Rigasa community; aiding evidence-based and targeted intervention for corporates, government, NGOs and concerned individuals. The long-term purpose of the survey is to help in creating a strategic synergy between education and community development through boosting literacy, which should consciously serve as foundation for improving socioeconomic prosperity, creating political and rights awareness, and advancement in technology and innovation – in order to ultimately rid the Rigasa community of entrenched crime, inter-generational poverty, violence through dysfunctional youth behaviour, etc.

Based on data collected, and interaction with staff, students, community leaders and elders, and members of PTA of all 7 schools; it is evident that while enthusiasm and demand for quality education are high, supply is grossly inadequate. It is also clear that public primary school education in the community, as it is largely in Nigeria, is under-funded, neglected and characterized by infrastructural decay, shortage of classrooms and toilet facilities, lack of instructional materials, absence of ICT-aided teaching/learning, and most importantly, inadequate teachers and teaching capacity.

For instance, as at time of surveying the community education system and facilities, the schools collectively had 14, 583 pupils, 63 classrooms, 33 toilet facilities, 225 academic and non-academic staff, largely no furniture, and not a single computer; while needing addition of at least 95 teaching staff, 225 classrooms, 60 toilet facilities, drinking water, and libraries, or a central library system. One of the schools, UBE Abuja Rd Primary School Rigasa, had 2,500 students, 20 teachers, 6 classrooms, no toilet facility and no access to drinking water. Furthermore, student-to-classroom ratio at the school is 400:1, and student-to-teacher ratio is equally appalling at 125:1 (due to this pressure, the school operates in shifts).

Following that, I organised the data into a report and submitted it to offices of those directly responsible for education in the state i.e., the Kaduna State Ministry of Education (MoE), and State Universal Basic Education Board (SUBEB). Since then, I have met formally with all levels of staff at the MoE and SUBEB including an Assistant Deputy Director, a Deputy Director, a Director, the Executive Chairman of SUBEB and the Commissioner of Education (yes, the civil service is unhealthily bloated).

I have also taken up the opportunity to speak with State and National Assembly members representing Igabi LGA at non-formal occasions — all of that in a bid to urge them to fulfill their respective duties on education, some of which are captured as recommendations in the report consisting of: constant and high-level capacity building for teachers; providing more, but qualified teaching staff; setting up a central library and ICT center to serve the schools and the entire community; bringing back social and extra-curricular activities; providing clean drinking water, textbooks and other teaching/learning resources; building additional classrooms on the relatively standard ratio of 1:40; and increasing toilet facilities, etc.

Other recommendations I verbally stressed to the officials are the need to set up a database that captures data of girls in all 7 schools in order to track their respective progress and guide them to transition to secondary schools – as that’s the first and best form of affirmative action capable of bridging existing literacy, opportunity, and achievement gaps between girls and boys, and women and men. Also — and with due consideration for economic and population disparities between states — the need for Kaduna State Government (KDSG) to replicate and adopt best practices from states like Rivers (reportedly built 500 model primary schools, each with 20 classrooms, ICT facility, and employed 30,000 teachers) and Osun (put opon imo, digital educational tablets, in the hands of secondary school students, which is also saving the state N8.4 billion annually on textbooks); reason being, a child in Osun that is provided with all the resources required to excel academically has a better shot at success against a child in a random school in Rigasa, Kaduna, whose school has not even been provided with chalk, not to speak of personal textbooks. (Comparatively, situations/policies like these are capable of leading to intra/inter-regional socioeconomic disparity which may be beyond the corrective capacity of affirmative action).

Let’s just say that one-year on, and I am still following up. I have emerged from many meetings jaded, armed with vague promises, requests to come back for further meetings, or referred to other offices; but without a strong or concrete commitment from the 2 state agencies (so, what to do?). What is clear is that, a lot won’t get done in terms of fixing education, or anything at all, if enough people do not demand it because those in government capitalize and literally feed off our collective apathy. Also, policy (and the constitution) largely favours and intensifies lack of accountability in basic education.

For instance (and pardon the digression, but it is relevant to explore basic education in broader policy context), a recent article in Leadership reported that 31 (minus Kaduna) out of 36 Nigerian states refused to access N48 billion of the Universal Basic Education (UBE) intervention fund by not paying the requisite counterpart funding and fulfilling other conditions. Sadly, that did not generate demands for accountability across many states; neither did it give reason for the public to seek a more stringent review of the UBE Act that would tackle fundamental, problematic and obvious, but rarely confronted issues that compromise children’s right to free basic education.

Consequently, we need a reviewed and strengthened UBE Act to make it: (1) incumbent, not optional, upon states to access and judiciously utilise the basic education intervention fund; (2) otherwise, we should explore possibility of engaging alternative administrators for same (especially in the case of defaulting states). This might require us to do some tinkering with the constitution, but so be it, since we’re in crisis mode where (basic) education is concerned; (3) considering that state executives are shielded from legal liability while in office due to the much-abused immunity clause, failure to access and/or judiciously utilise UBE funds should be made explicitly impeachable, i.e., unless if states have (and do utilise) alternative sources of funding; (4) SUBEBs across the country should be directed to respectively setup content-rich websites where information on basic education visioning, projects and spending can be accessed with the click of a mouse; and (5), Houses of Assembly need to adapt/localise the UBE Act (and the Child Rights Act), and define terms of operation for their respective states. They also need to intensify oversight functions on basic education.

Also, we need to clear the convenient ambiguity surrounding ownership and administration of basic education at the sub-national level. It does not make sense to keep saying that administration of basic education is, constitutionally, the responsibility of local governments, when they (LGs) lack autonomy, access to funds and the expertise to execute those duties. If state governors want to control education funds, they have to satisfactorily perform the duties that come with the funds — besides nothing stops the effort from being harmoniously collaborative, or as partly stated earlier, administration of basic education should be done in a PPP-capacity with the private sector playing the dominant role.

Having said that, Kaduna is 1 of 5 states that did not default in paying the counterpart funding requisite for accessing the FG’s matching grant. A search through the UBEC website reveals that in 2013, the sum of N1, 030, 797, 297.30 was allocated to the state – and by inference from the terms of the grant, the sum likely doubled. Also, according to a report/list cited in SUBEB News: A Publication of the Kaduna State Universal Basic Education Board (VOL.5 NO 1 JAN 2014), KDSG in 2013 spent a total sum of 1,626,098,787.58 (I’m sure there’s a logical explanation for the disparity between the figures) on 157 rehabilitation and expansion projects in 23 LGEAS. Sadly, none of the 7 schools I advocated for made the list of 157 interventions.

A sampling of the 157 projects — which seem rather ad-hoc and lacking in synergy — and their respective costs leaves a not so sweet taste in the mouth. For instance, a block of 4 classrooms with 2 ‘VIP’ cubicle toilets in UBE Ungwan Angah, Jema’a LGEA, cost 9,976,410.15; construction of a 4-classroom block in Akpon, Sanga LGEA set KDSG back a whopping 9,103,883.25, while a 3-classroom block in UBE Kuyer, Kagarko, was contracted for 7,063,827.75. In tandem with our apathy, I have so far not seen/heard any counterclaims or independent audits seeking to verify, praise, disprove or even challenge the 2013 intervention. We can therefore assume that in the case of improving education for the year 2013, Kaduna State excelled.

Personally though, I had hoped to read of projects conveying some sense of careful and strategic planning — something like what Osun and Rivers states are doing; projects seeking to leverage education as the tool for development and correction of social ills and imbalances; projects suggesting that handlers of education understand that dire social consequences go with bad spending of even a kobo budgeted for education, and vice versa. Really, that list should have contained projects that would show, at a glance, that we are consciously grooming the labour force, leaders and conscience of the future.

A few short examples of such projects, especially for a place like Kaduna that is fraught with mutual suspicions and intolerance could have been and still could be:

(1) Determining how best to use public schools to patch the sectarian rift that has engulfed and divided the state — Rigasa and Sabon Tasha are reportedly segregated along Muslim and Christian lines. Maybe creating social, but non-competitive interaction between schools from both communities could help in bringing the people back together?

(2) Another project, albeit a bit audacious, could entail taking an entire community and meeting a lot of its educational needs ranging from enrolment, to dropout, to improving facilities and providing teaching/learning resources and training for its teachers. Wouldn’t that beat a disjointed strategy of putting a block of 3 classrooms somewhere and neglecting the fact that children in same schools don’t have textbooks and enough competent teachers, or that possibly, half of children within that community are out of school – how else can we have massive infusion of education across communities?

And (3), if for instance we set up a central ICT education resource center that would give children access to materials contained in an improved Nigerian curriculum, audio-visual tutorials, extra-curricula subjects, past questions and other practical exercises; wouldn’t that aid learning, encourage reading, help to partly eliminate issues of teacher incompetence, generally broaden access to education within communities, and even save the state some money in the long run?

Sadly, that didn’t happen in 2013 (maybe we could push for it in 2014?), but at least some schools got touched-up with a fresh coat of paint – literally, at the cost of our children’s future. As for Rigasa schools, we should find out how selection of schools that benefit from government intervention are made, and concentrate on getting 2 or 3 of my Rigasa primary schools on the list of projects for 2014. I’m actually counting on the Kaduna state government to, with or without prompting, launch a far-reaching intervention in Rigasa community education, as that will serve as much-needed catalyst for development. In the interim, members of the community, including yours truly, have come together and are doing all they can to save Rigasa schools — more to come on that.

________________________________________________________________

Disclaimer

It is the policy of Newswirengr not to endorse or oppose any opinion expressed by a User or Content provided by a User, Contributor, or other independent party.

Opinion pieces and contributions are the opinions of the writers only and do not represent the opinions of Newswirengr